A trip to the ancestral homeland reveals new aspects of Kashmir. The canals, water lilies, vegetable markets, the sun rising over the mountains, the traditional houses, and the rhythm of daily life capture a culture of beauty, tradition and sophistication.

By: Namrata Wakhloo

have traveled to Venice several times and gone for gondola rides on the Grand Canal. During my trips, I always wondered how close the water was to the centuries-old mansions and how beautiful they looked with the soft waves of water splashing against them.

Little did I know that we have something more alluring in our own homeland. Last month, I visited Srinagar and stayed in a hotel on the banks of Nigeen Lake. This neighborhood is known as Rainawari. Even though I grew up in Srinagar, I had never been to this part of town. Of course, I had often heard from my parents about the backwaters of Rainawari, and how people in the olden days would use these canals to commute.

In those days, water transport was one of the most convenient modes of transport in the old city. This was thanks to Kashmir’s 15th-century ruler Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin Badshah who built a network of canals in the Kashmir Valley. The most prized canal was Nallah Mar that has proved to be a blessing for Srinagar. Over the last century, roads have replaced the waterways. Yet canals remain a key part of Srinagar and Kashmir.

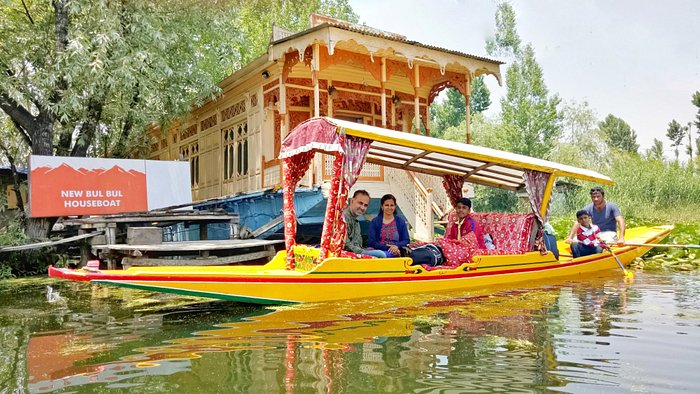

A memorable boat ride

During my trip, a boatman was available at the hotel. One evening, he took me on a ride in Nigeen. “Do you think we can go to the Rainawari backwaters from here?” I asked him during my ride. “Certainly,” he said with a smile, and so we agreed to start at dawn the next morning. We visited the floating vegetable market first and then we saw life in Rainawari along its main canal.

Naidyar is the canal that connects Dal Lake to Nigeen. As we moved silently through the water, the sun was rising behind the peaks of the Zabarwan Range. The vegetable sellers had wrapped up their morning deals and had congregated together. I settled with them and had a hot cup of kahwa—traditional Kashmiri tea—that I have grown up drinking. This kahwa was different. We make our kahwa with cardamom and a few slivers of almonds. I was apprehensive about this kahwa because it was garnished with rose petals and some other herbs too.

My fears were misplaced: “not bad,” I thought after taking the first sip. The boat made its way through the canal, which was covered with water lilies. It was too early in the day for the flowers to bloom. Still, the lily pads were beautiful in the morning sun.

On both sides of the canal, there were some regal houses built in the old Kashmiri style with thin clay bricks and wood. Many of these vintage houses towered over the water with one or more dubbs—covered balconies typical of traditional houses—overlooking the water. I could not help but admire how tastefully people in Srinagar had built their homes more than a century ago.

Things are changing

During my boat ride, I observed that these beautiful traditional houses were being replaced by ugly concrete monstrosities. Some houses were just houses, not homes. Their owners have probably fled Kashmir for good. As is well known, Hindu Kashmiri Pandits left the valley in early 1990 to save their lives from Islamist militants. Many Pandit houses still remain empty.

What Lies Behind India’s Bold Bet on Kashmir?

I thought of the large and jovial families that were once the life of these now empty homes. The men and children would have taken boats to work or to school, mothers would have finished cooking the freshest vegetables bought from the Dal Lake and then probably sat on their balconies or on windowsills for a round of gossip with the neighbors.

Just as I was reminiscing, I saw a flower-laden boat, silently making its way towards me. The flower seller was a chirpy young man who knew how to make an instant connection with a stranger. His tawny skin made it obvious that he spent most of his day rowing under the sun. He sold fresh flowers that are grown in the floating gardens of these lakes, especially the pink lotus. He also had little packets of local flower seeds, considered exotic in the North Indian plains. Although he had a good spiel, I did not buy the seeds. Most of the variety he was selling would not grow in the Indian plains where I now live. After some minutes of cheerful banter, we bid each other goodbye.

I saw temples and mosques not far from the banks. The boatman pointed to a beautiful Shiva temple on my left. It had steps from the water leading to it. I didn’t even have to shut my eyes to see the picture of Pandit men and women in their pherans, walking down these steps at dawn for ablution and offering prayers to the Surya, the sun god. I asked the boatman if we could halt here briefly so that I could pay a quick visit to the temple. He was more than happy to stop, but when we reached the steps, we noticed that the temple gates were locked. The boatman suggested that I should try to visit the temple using the roadside entrance. This place was called Jogi Lankar.

Local delicacies and parting thoughts

The Dal and Nigeen lakes are very popular for nadur—the lotus stem/lotus root that is harvested from them. Nadur is part of the staple diet of Kashmiris. It is usually cooked along with meat, fish, or vegetables like kohlrabi and other kinds of turnip. Often, nadur is a standalone dish too.

We rowed under quite a few bridges, some new and some old, made of bricks and wood. Business continues to thrive around these bridges. I crossed a small factory that made the famous Pashmina shawls and a few rows of shops. Since it was morning, they were still closed. A trader was ferrying sheep on a boat. There were kotarbaaz (pigeon-keepers) tending to their pigeons with a long barge pole. And a lone young man here and there, patiently sitting on a jetty, fishing. It was a little past 7:00 am and the neighborhood was slowly coming to life. I could see a few ladies working in the kitchen with neatly arranged shining pots and pans, as our shikara—traditional Kashmiri gondola—passed under the kitchen window.

As the boat ride was ending, it was time to head back to the hotel for a nice breakfast. The boatman, knowing the Kashmiri love for the local bread, asked me if I would like to get some. He quickly hopped onto the bank and disappeared between the houses to reach the kandur, the local baker. The boatman was back in no time, with a bag full of girda—a sort of flat round bread—baked in a tandoor, a traditional clay oven. Girda tastes best smeared with butter accompanied by a hot cup of chai, traditional Indian tea.

Unfortunately, lake water in Kashmir is getting heavily polluted with sewage and domestic waste from the houses and houseboats. I have seen some houseboats using sustainable bio-waste management systems for their toilets. Sadly, this is rare and voluntary. Kashmir needs an intensive and effective mechanism to handle waste from these neighborhoods. Otherwise, we risk losing these water bodies that form the soul of Srinagar.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect our editorial policy.