I the afternoon of 29 August 1938, Prime Minister Narasimha Gopalaswami Ayyangar was returning from office to his residence in Srinagar when his car was attacked by a crowd of agitating men and women at Amirakadal Bazar. Ayyangar, accompanied by Home Minister and another colleague, was injured.

While fleeing from the scene his car ran over a protester and grievously injured him. The crowd was protesting against the arrest of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and other political leaders who had made speeches against the Government at Hazratbal on the previous day and were now assembled for a similar protest at Maisuma in the uptown.

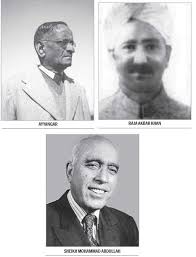

The trouble in Srinagar had started soon after rejection of an appeal by the High Court against conviction of Raja Mohammad Akbar Khan, then a senior Muslim Conference leader from Mirpur, in a case of sedition. Earlier on 16 June 1938, Khan had been sentenced to 3 years rigorous imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 100 by Sessions Court for making, what the court termed, a seditious speech at Jammu in 1937.

The rejection of appeal by the High Court was followed by series of incidents – demonstrations, fiery speeches, slogan shouting and stone pelting by people, and, in turn, arrests, cane-charging and firing by the police – resulting in some fatal casualties.

Besides a host of prominent political leaders, over a thousand people were taken into custody. The arrest of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah added fuel to the fire. For weeks, Srinagar was on the boil. All major towns of Kashmir including Anantnag, Baramulla, Sopore, Ganderbal and Bandipora also witnessed public demonstrations and government reprisal. Poonch and Jammu too were rocked by protests and punitive police action.

The Jammu Kashmir Muslim Conference, established in 1932, was still a united house although process of its dissolution and replacement by a ‘nationalist and secular’ party had long been set in motion. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, focused on political conversion of the party, was not able to gather majority support within its ranks. Raja Mohammad Akbar Khan was in the forefront of, what he believed, broad-basing the Muslim Conference by brining non-Muslims into its fold.

A public meeting – the last by the united Muslim Conference in the winter capital – was held at Eidgah Jammu in June 1937 where Khan moved a resolution to convert the Jammu Kashmir Muslim Conference into the Jammu Kashmir National Conference. The resolution failed due to strong opposition, leaving Khan in a sour mood in which he made a fiery speech against the Dogra rule.

“MeriawazchaleeslaakhlogunkiawazhaijoHari Singh kemehhalaat se takrakarunhainpaashpaashkardegi (My voice is the voice of four million people [of Jammu & Kashmir] which will strike against the palaces of Hari Singh and raze them to the ground),” Khan roared.

A case of sedition, first in Jammu Kashmir against a political leader, was filed against him under Section 124-A in the court of Sessions Judge Jammu, Haveli Ram Malhotra, who sentenced him to imprisonment with fine.

An appeal was filed in the High Court against Khan’s conviction. Dr. Mohammad Alam, a prominent lawyer of Lahore nicknamed as Dr.Lota for frequently shifting loyalty from the Muslim League to the Unionist Party to the Majlis-i-Ahrar, appeared for Khan. The Court maintained the conviction but reduced the sentence to 18 months rigorous imprisonment and fine to Rs. 25. Khan’s colleague in the Muslim Conference, Allah RakhaSagar, made a sarcastic versified comment on the rejection of the appeal: MirpurkeMujahid Akbar baatkartaythayiddi’akarke Appeal bhimustaradhueebaatbhikhoyiiltijakarkay (The struggler Akbar of Mirpur whose words carried conviction lost both his appeal and face by making a request [for reversal of his conviction). Senior politician and writer, KrishenDevSethi, however, asserts that Khan was not in favour of filing an appeal and Sagar’s sarcasm as he later wrote, was directed against Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah who had decided to move the High Court against Khan’s conviction.

By the time the order of dismissal of appeal came, Abdullah in anticipation of dissolution of the Muslim Conference, had since warmed up to Kashmir’s non-Muslim leaders like PremNathBazaz, JialalKilam, KashyapBandhu and Budh Singh who joined the protest meetings held in support of Khan. During these meetings, speeches were made whose anti-autocracy subject matter, the Government alleged, were “untrue and scurrilous things”.

People defied law and the judgment of the High Court and repeated passages from Khan’s speech “from place to place and incessantly”. The Government responded with banning, for one month, processions and public meetings within the municipal limits and issuing notices to some leaders against their being bound over for good behaviour under Section 108 Cr PC. The measures had no effect on the ground.

Two days after 26 August 1938 when the District Magistrate issued prohibitory orders, a public meeting was held outside city limits at Hazratbal where speeches against the Government were made and people “incited to defy the law openly”.

The speakers besides Abdullah, included PremNathBazaz, KashyapBandu, JialalKilam, Mohammad SayeedMasoodi and Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq. Next day, on 29 August, defying prohibitory orders, a public meeting jointly attended by the leaders of the Muslim Conference and the minority community was held at Maisuma. Police swung into action and arrested Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Budh Singh, KashyapBandu, Mohammad SayeedMasoodi, Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq, Ali Mohammad and GhulamMohiuddin(Identified by KrishenDevSethias Ali Mohammad Tariq and GhulamMohidduddinHamdani). The arrests were followed by protest demonstrations and shutdown in the city. Traffic at Amira Kadal was impeded.

In the afternoon, amid disturbances at the city center, Prime Minister Ayyangar, accompanied by Home Minister Sir AbdusSamad Khan and Minister in Waiting NawabKhusru Jung, left his office for home. When his car reached Amira Kadal Bazar it was mobbed by agitating people who pelted stones at the vehicle and broke its glasses. Ayyangar sustained injuries by broken pieces of glasses. His car sped away from the scene but in the process ran over a protester, Mohammad Rajab, dragged him on for about 500 feet until an Englishman stopped his car in the middle of the road to obstruct passage to the Prime Minister’s vehicle and bring it to a halt. Rajab was seriously injured and sustained a 2 inch deep and 25 inch long wound. He was admitted to the Mission Hospital in a critical condition.

The Government blamed it on “a mob of goondas, urchins and some women” who, it alleged, attacked the Prime Minister’s vehicle, “broke the glasses and caused damage to the mudguard and other parts of the car with stones which were flung at the car… The Prime Minister himself received a shower of splintered glass all over his person but luckily escaped any substantial injury.”

About the Prime Minister’s car running over a protester and seriously injuring him, the official press release explained it away thus; “A number of them [protesters] tried to stop the car and force it back and one of them apparently got on to the bumper in front of the radiator and, in trying thereby to hold on to the moving car, got entangled therein. The car however proceeded on its way but the man clinging to the bumper being not visible to the driver or the inmates of the car was dragged on for some distance. He sustained severe injuries which are being attended to in the Mission Hospital.” No further information was given about the injured person in the subsequent press releases.

“He was a young boy. I do not remember exactly but perhaps he succumbed to his injuries”, recalls KrishenDevSethi.

In the evening, another protest meeting was held at the DhanjibhoyAdda, a Tonga station near the Polo Ground opposite the building named after its Parsiowner, Dhanjibhoy, where more speeches were made and more people arrested. In all, 65 persons were taken into custody on 29 August.

As is the wont of all repressive regimes, Maharaja Hari Singh’s Government dismissed the public anger as:“engineered by a small clique and that the vast majority of the members of all communities condemn them without reserve and desire that this exhibition of lawlessness should be put down with a firm hand as quickly as possible.”

Notwithstanding the Government crackdown, protests continued and business remained affected especially in the city center with people holding demonstrations and shouting slogans. Passage to any vehicle carrying a Government officer was particularly obstructed.

In different parts of the city funeral processions and parades of wounded people allegedly killed or injured in cane charge by police were taken out. The Government, however, said no person was injured or killed as “no can charge of any magnitude was made”. The police claimed that in one case a dispersed procession left the ‘dead body’ on the road and when the blanket covering it was removed it turned out to be “a bundle of grass” with red colour sprinkled over the bier. “The bundle and the blanket”, the Government claimed, “is with the police.”

Similarly, “a so-called wounded person on receiving a poke from a policeman jumped off the bier and took to his heels”, it added. The Government continued with arresting people. It alleged that “Goondas” in the city were responsible for drilling boys for the processions. Overnight, two persons were arrested for allegedly attempting to burn the Nawakadal, a bridge over the Jhelum in old city.

Angry demonstrators pelted stones at police and army in different parts of Srinagar. The situation seemed turning difficult for the government when the District Magistrate issued a stern warning that:“throwing of stones on the military or the police might result in the latter firing on the persons throwing them and if the people persisted in stone throwing punitive police would be imposed on the Mohallas concerned.”

Punitive action was also threatened against localities where shouting of slogans occurred. One of the notable features of the protests was the strike by Tongas which then were the main mode of transport in the city. The Government admitted that the strike had caused inconvenience to visitors.

In Baramulla, protesters attacked and injured the Wazir (Deputy Commissioner) of Baramulla and the Superintendent of Police. The Government’s helplessness was manifest in the President Srinagar Municipal Committee’s warning to his Mohalla Officers (Wardens) that they would be held responsible for “controlling the batches of unruly boys who move about in the streets and lanes shouting slogans.” They were forced to take the responsibility of maintaining peace in their respective areas and in the event of their failure, provide lists of the parents of delinquent boys to the government.

On 31 August, seven leaders arrested two days ago were sentenced to different periods of imprisonment and fine. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah (mentioned in official press notes as Mohammad Abdullah Sheikh or Mohammad Abdullah only), Budh Singh, KashyapBandu, Mohammad Sayeed (Masoodi) and Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq were sentenced to six months imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 25 each. Ali Mohammad was sentenced to six months imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 20 while GhulamMohiuddin received a sentence of one month’s imprisonment. During the day, 47 persons were arrested from different parts of the city. Other leaders like ChowdharyGhulam Abbas, PremNathBazaz, Mirza Afzal Beg and JialalKilam were also arrested at different places and on different dates.

As the agitation gained momentum, a printed poster titled ‘National Demands’ with ten prominent leaders from Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities as signatories, was “broadcast and published in various parts of the country” declaring the movement as “nation-wide” and all classes of the people “participating in it with the fullest consciousness of the issues it involves.” The poster described the ultimate goal of the movement “to bring about complete change in the social and political outlook of the people and to achieve a Responsible Government under the aegis of the Mahraja.”

The publication and circulation of the poster “proved to be a signal for measuring the swords between the fighters for Kashmir’s freedom on the one side and the alien and autocratic Dogra rule on the other.” The Government felt that the poster could reinforce the ongoing agitation. In a press communiqué issued the next day, among other things, it blamed “Mohammad Abdullah Sheikh and his associates” of committing offence under Section 124-A and repeating passages from Raja Akbar Khan’s seditious speech from public platforms at different places and timings, and carrying on a vilification campaign.

On 2 September, one person was killed due to police action at Maisuma on the previous evening. His body was kept at Khanqah-i-Moalla and people refused to hand it over to the police for postmortem. The Government denied that he died due to police action, for the “only injury on his body was an abrasion on the skull which according to the doctor would not cause death”.

However, it did not give out the cause of his demise. Later, the body was taken in a procession for burial. Besides earlier branding protesters as ‘goondas’ and ‘urchins’, a frustrated Government, reacting on the incident, blamed the protest demonstration at DhanjibhoyAdda and stone pelting at Maisuma on the previous evening on “a mob of Muslims” and “rowdies of MaisumaMohalla”. It claimed that 21 policemen received injuries, some of serious nature.

At Soura, birthplace of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, a police party was attacked with stones, injuring some of them including a Head Constable. The attackers then “took to their boats and concealed themselves in the islands of the [nearby] Anchar Lake” leaving the police clueless about their location. Two days later, it claimed 8 persons involved in the incident were arrested. For days, the Khanqah-i-Moalla remained center of large protests and speeches against the Government. The Statesman reported that college and school students had joined the ongoing agitation in Srinagar.

Reports of police highhandedness kept pouring in from different parts of the Valley. There were allegations that victims injured in police action were denied treatment in hospitals; residents of Maisuma and GawKadal were looted by police, and repression on women was committed at Ganderbal leading to the death of a pregnant woman. These allegations formed consistent part of speeches made from public platforms. The Government, in traditional style, termed them “gross and malicious lies.” In an atmosphere of protests, slogan shouting, police action and the resultant chaos, several rumours were afloat in the city keeping the Government on tenterhooks.

At times, it had to issue press communiqués to deny ‘rumours’. On 4 September, it rebutted a report seeking to circulate an impression that Government had failed to control the situation, that Kashmir’s Governor and Senior Superintendent of Police had been transferred out.

After completing six months imprisonment, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was released on 28 February 1939. By this time, ground for conversion of the Muslim Conference had been cleared and major impediment in the persons of ChowdharyGhulam Abbas and his close associates had been overcome.

Pertinently, when political leaders were arrested during the 1938 agitation, Abbas and Budh Singh were lodged in the Reasi Jail where the latter brought the former around on the issue of conversion of the Muslim Conference.

Earlier, Abbas had vehemently opposed the move to dissolve the party. (He rejoined the Muslim Conference two years after it was revived in 1940.) On 11 June 1939, at a specially convened meeting at Pathar Masjid Srinagar, Abdullah was successful in securing an overwhelming vote for the conversion and renaming of the party as the National Conference. When Raja Akbar Khan was released from jail, his dream of demolition of the Muslim Conference and building over its debris a secular National Conference had been realized.

“His joy knew no bounds over this development”, writes Krishen Dev Sethi in his memoir, Yaad-i-Rafta. Another politician for whom the development was “the happy news” was Prem Naz Bazaz. For Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, to quote from his autobiography, it was “a dream-come-true” moment.

Khalid Bashir Ahmad