The former chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir says the central agency’s raids on separatists in the Valley are not political but based on real evidence.

In Srinagar, after months of anti-government protests and encounters between militants and security forces, the spotlight has turned to other matters: the threat to the state’s special status and the National Intelligence Agency raids on separatist leaders. At the same time, the Centre is talking about being open to dialogue with separatists and the state government is releasing tourism videos to shift the focus away from Kashmir as a conflict-hit region and draw attention back to its popularity as a holiday destination.

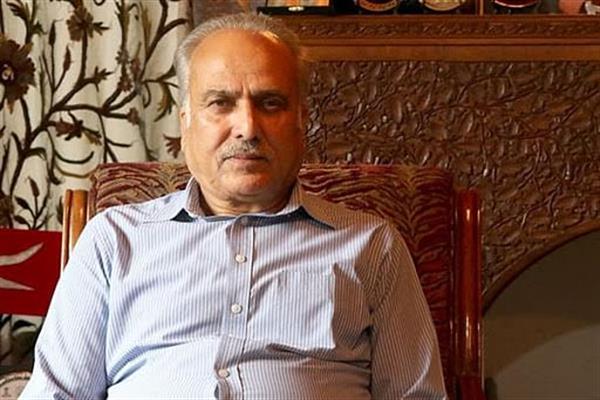

Amid all this, the poor turnout and violence during the Lok Sabha bye-elections in the state in April pointed to a growing disillusionment with the political process. Is the political mainstream, or parties which participate in elections, still in crisis? Omar Abdullah, chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir from 2008 to 2014 and working president of the National Conference, answers this and other questions in an interview.

You recently responded to Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti’s first tweet, where she posted the government’s new tourism video. What did you think of the video?

It shows Kashmir in the context that we would like it shown. Kashmir is always shown through the prism of the trouble in the last three decades. So anything that helps to change the narrative. In today’s day and age, nothing does that better than social media. If you could put out something that goes viral and gets people talking then great. Of course, one video alone is not going to fill hotels. But it’s a start. We’ve had two disastrous seasons now. Let’s hope something improves next year.

But did it not make you uncomfortable, the image of this ever-smiling Kashmiri, always at the service of tourists from the mainland, no matter what he’s gone through?

I mean, it’s a marketing video. There are many facets to life here. Tourism is an important part of our economy. A lot of livelihoods depend on it. One can’t blame the government for trying to put its best foot forward. I don’t think we should read more into the video than an effort on the part of the government to try and get more people to visit.

There’s been this criticism, about successive state governments and the Centre, that they take cover in tourism instead of addressing political questions. Prime Minister Modi, for instance, asked the youth to choose between “tourism” and “terrorism”.

All that’s rubbish. I spent six years as chief minister very carefully distancing tourism from the perception of a return to normalcy. When we start looking at things from this equation, tourism or terrorism, we become our own worst enemies. Because we are then incentivising attacks on tourists at the hands of those very terrorists. I remember, in 2005-’06, when tourism numbers started looking up, then Chief Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad saab’s government also making similar statements: tourism has returned to Kashmir, normalcy has returned. And no sooner than those statements started, you had attacks against tourists. Buses had grenades thrown on them. Mughal Gardens had IEDs and bombs placed outside.

What is your opinion of the recent National Intelligence Agency raids and arrests? They have cast a widening net, involving not just separatist leaders, but also scholars, traders, mainstream politicians and photojournalists.

It’s a legal process. I’d like to believe that the NIA is an independent investigative agency, and that this is being done on the back of credible, realistic evidence. And this isn’t political.

So you don’t give credence to the perception that this is being done to delegitimise separatist demands?

If the NIA proves that these people have taken money, and have not accounted for it, then they are the ones who are responsible for delegitimising the struggle in Kashmir, not the NIA. I think the people have a healthy suspicion of the conduct of some of these leaders. Wasn’t too long ago that these separatist leaders called a shut down because of the NIA arrests and it was an absolute failure. It was almost as if it was a normal day in Srinagar. I have never seen a poorer response to a shutdown call by the separatists. So I don’t think the blame lies with the NIA.

The folklore is that…

Look, don’t go by folklore. There are many theories. One of the theories is that this is basically a ruse to get some of these leaders to Delhi so that you could have a dialogue without exposing them. We as a community are great at creating conspiracy theories.

Home Minister Rajnath Singh recently said he was “ready to talk to everyone” in Kashmir. But what does it mean when you have Hurriyat leaders behind bars and you talk about talking to them?

Well, obviously that’s a contradiction, isn’t it? If it is an independent investigation then the law must follow its own course, and any dialogue will have to be disconnected from that.

The challenge is converting the intent of dialogue being unconditional into an actual unconditional dialogue. No sooner does New Delhi suggest that they are willing to talk without any preconditions than you find the Hurriyat starts placing preconditions. Suddenly they want a tripartite dialogue. And they misrepresent history to suit their opinions. I saw a statement yesterday by Mirwaiz [Umar Farooq, leader of a faction of the Hurriyat] that Prime Minister Modi should follow the Vajpayee method. But I don’t recall Prime Minister Vajpayee giving any sort of forward movement to a tripartite dialogue.

A tripartite dialogue basically means that all three parties will be at the table at the same time. Which has never happened and I don’t expect it to happen. If what the Mirwaiz means is that Pakistan should be engaged and Jammu and Kashmir should be engaged, but not necessarily in the same room, then, of course, we all agree with that. You can’t say we won’t talk to Delhi unless Delhi is talking Islamabad. The moment you start setting conditions for dialogue, so will Delhi and then the dialogue will go nowhere.

Do you think the debate around Article 35A, a law which reserves special rights and privileges for “permanent residents” of Jammu and Kashmir, has turned the conversation away from azadi to special status?

There is this perception that Article 35A has very cleverly got people talking about a solution within the Constitution rather than outside it. At the same time, the situation on the ground hasn’t changed. You still have encounters of militants almost every day. It’s not as if, just because the talk has shifted, the situation has changed as well. But it is interesting that for the first time, perhaps, separatists have called for a shutdown to defend a facet of the Indian Constitution.

Do you think this agitation on Article 35A has consolidated political forces in the Valley? Leaders across Kashmiri parties, both separatist and mainstream, have come together on it.

It’s not as if suddenly the People’s Democratic Party and the National Conference have made common cause beyond just Article 35A. And the same goes for the separatists. Their political goal differs from ours. Just because we agree that Article 35A should not be tampered with, doesn’t mean we agree on anything else.

This April, the National Conference won the Lok Sabha bye-elections by quite a large margin. Except voter turnouts were very low, about 7%. What does such a victory mean?

Well, on one hand, it re-establishes National Conference’s presence in Parliament. On the other, it also brings sharply into focus the decline in the overall environment in the state since the BJP-PDP alliance came into existence. In Anantnag you weren’t even able to hold an election. No matter how good the videos are that you put out, the ground reality is that you are unable to hold a bye-election to a parliamentary seat that was vacated by the current chief minister, and a seat for which the chief minister’s brother was the candidate. So our satisfaction at establishing our presence in Parliament was tempered with a strong sense of just how bad things are in the Valley at the moment.

The bye-election seemed to establish that the political mainstream faces a crisis of legitimacy. They weren’t even able to hold rallies in most places.

The fact is that it wasn’t our workers who didn’t want to come out. At the end of the day, the onus lies primarily with the Central and the state government, and of course, the Election Commission, to create a conducive environment for electioneering and they failed. The National Conference worker in 2014 is still a worker today. It’s not as if they’ve suddenly jumped ship or decided to become separatists. So the failure isn’t of the mainstream on the whole, the failure is on the government.

But at the grassroot level, there has been a series of resignations, from both the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party, saying they have given up mainstream politics.

That is basically a means of staying alive in an otherwise difficult environment. Again, it is a failure of the state government that a mainstream leader would feel threatened enough to distance himself from a political process that he was until yesterday willingly a part of.

But given the voter turnouts are so low, isn’t it clear that there is a disconnect between the public and the parties?

If the voter turnout had been 7% without any law and order disturbances, I would have been extremely worried. In a lot of places people were unable to come out and vote because of the prevailing disturbances. Otherwise, you tell me, what accounts for a constituency like Chrar-e-Sharief, which in the 2014 assembly elections probably had a turnout of 55%-60%. In this parliamentary election, it was in single digits. Now you can’t tell me that 60% of the population, over the course of two years, have suddenly decided that they don’t want to be part of the mainstream. And this is a constituency that even in ’96, had a larger turnout than most other constituencies.

So, it would be shortsighted on our part to just look at the turnout, independent of the prevailing circumstances. Yes, the fact that the protests were as widespread as they were is a cause for worry. The fact that the youngsters felt the need to come out and disrupt the election process is something that we need to try and understand and draw lessons from. But to suggest that 7% is a reflective figure, that nobody else wanted to vote, I think would also be incorrect. There were a lot of instances where people told us that we wanted to vote but there were 10 people throwing stones outside our polling booths so we stayed at home.

It doesn’t help that you take a person who has now been proved to be a legitimate voter and tie him to the front of a jeep and parade him around villages.

On the subject of militancy, the police chief recently talked about the possibility of surrender. Under your government, there was a surrender policy but rehabilitation efforts failed and there were reports of police harassment. What do think were the gaps and what should a new surrender policy look like?

The biggest one is in terms of providing an economic safety net for these people. Police harassment is easier to manage. For us, the biggest difficulty was in terms of rehabilitating militants who came back from PoK [Pakistan occupied Kashmir] via Nepal. Because a lot of them came back with families, they had married Pakistani girls. So their nationality became a problem. But since 2014 that route has been closed so that chapter has been shut.

Is this government serious about surrenders and if they are, what is their surrender policy? Are you looking at resuming this move to allow people to come back from Pakistan, those who had gone across for training but haven’t been involved in acts of militancy? That will be a completely different policy. Part of this is what you do about their economic rehabilitation.

I guess the rehabilitation policy will also have to look at the severity of the incidents that they have been involved in. Somebody who picked up a gun 15 days ago, hasn’t been involved in any acts of militancy, but because they are now designated as a militant, their rehabilitation will have to be carried out. That will pose a slightly lesser challenge than somebody who has, say, been a militant for 10 years, involved in serious acts of militancy against security forces and others. You can’t have a one policy fits all sort of a set up.

I think for the moment the government needs to focus on trying to ensure fewer youngsters pick up the gun, and to start looking for a rehabilitation policy for those who have recently joined the ranks of militants. If we can bring some of them back, we can look at the hardened cases later.

Do you think encounters, where there are public protests now and sometimes even civilian deaths, are fuelling resentment against the state?

Well, sure. The fact that cordon and search operations have restarted this year after a very, very long gap, that adds to resentment. There is no easy answer to this. What do you do when militants have taken up positions inside a home or a building? You give them an option to surrender, if they don’t then unfortunately an encounter will follow. The fact that a militant is going to die in an encounter, I guess, is a given.

My worry is when civilians get caught up in encounter sites. We need to avoid large crowds gathering at these places. We have established systems of setting up choke points in rural Kashmir so that we stop the flow of people from one village to another, thereby not allowing large crowds to gather. But it requires constant monitoring and we need to keep honing the tactics that we use. But the idea is to lock down individual villages so that people can’t congregate at the encounter site.

Kashmir is still recovering from the 2016 protests, where many were killed, blinded or maimed. Going back to 2010, when there were protests and afterwards your government had ordered an inquiry into civilian deaths. Why was that inquiry report never made public?

I don’t know if that inquiry has even been completed. Till 2014 I know that the inquiry commission asked for periodic extensions in time which we had to grant. Because if we hadn’t then the inquiry would have ended without delivering any report or any findings, which we didn’t want because then it would have looked like an effort to whitewash everything. But after 2014, once the government changed, I don’t know what the current status is of that inquiry commission.

Could you not have asked for a time-bound probe?

All probes start out as time-bound probes, not just in Jammu and Kashmir. Unfortunately, while we do set time limits, it is for the person who is conducting the probe to actually adhere to them. That doesn’t really happen. That said, they are an important tool to establish what exactly happened and to take action if necessary. We have to live, unfortunately, with the delays.

One of the incidents that catalysed the protests of 2010 was the alleged fake encounter at Machil. Part of the legal process to prosecute those guilty is with the army now.

We are deeply concerned with the way even the army action now has been undone. The soldiers have been found guilty and punishments have been handed out. Those in the military court of appeals have been overturned. If justice is not seen to be done, even in a case where they have been found to be guilty, then what confidence will people have going ahead when unfortunately, we feel the need to take recourse to this similar sort of legal system?