By Rifat Mohidin

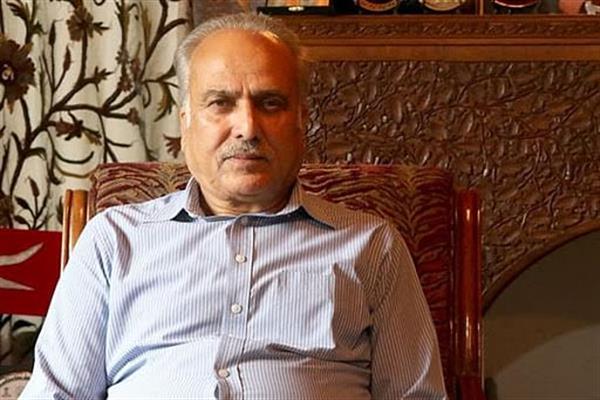

After decades of conflict and “disappeared people”, Kashmiri women are now making their voices heard, demanding to know the whereabouts of their missing family members. PARVEENA AHANGER shares her journey of wait and hope with Rifat Mohidin.

On 18 August 1990 we were sleeping at our home in Srinagar. The armed conflict was at its peak and the army would enter any home at any moment, and arrest people.

On 18 August 1990 we were sleeping at our home in Srinagar. The armed conflict was at its peak and the army would enter any home at any moment, and arrest people.

My eldest son Javiad Ahmad Ahanger had just finished school and was all set to go to college. He had decided to study commerce. He had even bought the books and his new college identity card.

In our neighbourhood, there was one militant with the name of Javiad Ahmad Bhat. That night the army had cordoned off the neighbourhood and they were loudly calling the name ‘Javiad’. When my son, who was asleep at home, heard the soldiers calling his name, he panicked and jumped out the window of his room, straight into an army trap.

That was the last day I ever saw him.

The next morning I went to police station to get him back. We lodged protests and filed a First Information Report. The police said Javiad had been hurt and admitted to an army hospital in Srinagar. They assured us that my son would be released. The next day I rushed to the hospital to see him, but I could not find him. They all lied to me.

My life changed completely after the disappearance of my son. I could not take care of my other two children; I did not guide them. My family suffered.

It became a routine for me from that day to go to police stations, jails and wherever I could go to find my son. I went to remote villages to look for him. When I returned home in the evening, I would find my feet had swollen up. I haven’t eaten daytime meals at my home for 13 years. Every night I had a hope that tomorrow I might see my son. That hope kept me going.

While going to the villages in search of my son, I found families, mothers and fathers like me, whose children or husbands were arrested like my son and never returned.

Disappearance is very painful. We don’t know what happened to our children, whether they are alive or dead. We are living between hope and despair. I thought, “We all have the same struggle, the same pain.” So I got them all to Srinagar and we started holding meetings at my Srinagar home.

One day one of the persons whose son is missing said that we should hold protests at some public place where people can hear our pain. So from that day, we hold our monthly sit-in protests at the commercial hub in Srinagar.

In 1994, I founded the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) so that we could fight for justice for the missing family members. There are no exact figures for how many people have disappeared in Kashmir in the last twenty years. There has been no complete research, but they are believed to be in the thousands. We are trying to document the cases from different villages in Kashmir.

We have tried fighting the cases in court but all the cases are pending; the army has some laws in Kashmir which provide them impunity from prosecution in situations like these. Still, we will never stop this fight; I won’t stop as long as I live.

Since 2000, I have represented the APDP’s cause internationally – in the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Chang Mai, Geneva, Cambodia and last year in London. The struggle is not going to be easy but I am committed to the fight. Many women died while waiting for the return of their sons. Now they have no one to fight their cases. I have promised these women that I will take their case forward like the case of my son. I have to fulfill their promise.

I have been socially cut off due to my fight for justice for my son, but I have a family in all those people who are on a journey with me to trace their family members. I share with them their grief and their joy.

Whenever there is a marriage or any occasion in the homes of these people, even in the far off villages of Kashmir, I make sure to go there and be with them. No one can understand their pain better than me, for I share the same pain.

Most of these families, whose male members were made to disappear in the two decades of conflict in Kashmir, have no men in the family, so it is really difficult for them to carry on. The women do not remarry as they hope that some day their husbands might return. These women are burdened by the responsibility of their children and the pain of separation.

– As told to Rifat Mohidin