In Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s push to supply electricity to every Indian household, connecting homes in the state of Jammu & Kashmir might be the toughest.

Along India’s violence-prone northern border, engineers and construction workers are hauling tons of high-tension wires and steel frames on pack mules across barren deserts and mountain ravines to electrify one of the country’s most inhospitable states. Still, the effort, budgeted to cost 48 billion rupees ($740 million), may turn out to be Modi’s most rewarding.

In some villages, winter outages persist for 20 hours a day even as temperatures dip to minus 35 degrees Celsius (minus 31 degrees Fahrenheit). Modi is counting on 24×7 power to both warm homes and hearts in the Muslim-majority state, where as many as 70,000 terrorists, security forces and civilians have died in independence-fueled clashes in the past three decades. Construction of key infrastructure in the Kashmir Valley may be helping.

“People understand the value of this project since very few large development projects are happening in the valley,” said Pratik Agarwal, chief executive officer of Sterlite Power Transmission Ltd., which is building the state’s first private transmission line. “We have been getting incredible support as power is something people can relate to — it’s something that everyone wants.”

Protests Subside

When the first equipment reached a spot about 40 kilometers (25 miles) from Srinagar, one of the state’s two capital cities, in May 2016, locals protested what they thought was the makings of an army camp. As an electrical substation emerged, opposition gave way. Now, two neighboring villages are squabbling over rights to get their name on it.

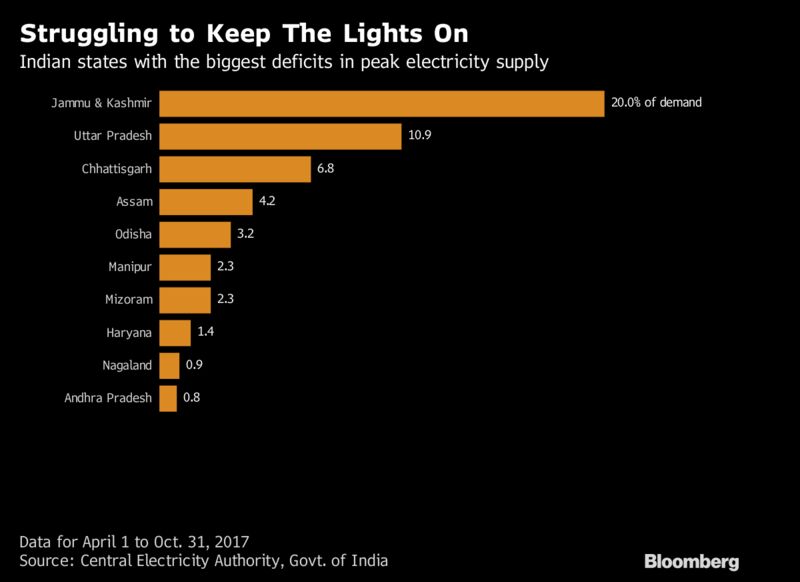

The enthusiasm reflects an eagerness for electricity in a state lacking a fifth of the peak energy it needs. It also points to infrastructure as a potential avenue for Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party to garner greater support from Muslim Kashmiris, some of whom have violently opposed the controlling force of New Delhi, 825 kilometers south of Srinagar.

Electricity shortages have long been a bane in the Kashmir Valley, and providing reliable, affordable, constant power could go some way in quelling unrest, according to Noor Ahmad Baba, dean of the school of social sciences at the Central University of Kashmir.

Baba traces a connection between lack of electricity and militancy, drawing from his observations as a youth in the late 1980s, when insurgency escalated in Kashmir.

‘Lot of Discontent’

“Poor electricity supplies not only deprive Kashmiris of education, employment and medical facilities, but also very basic things like entertainment and communication,” he said over the phone from Srinagar. “This leads to a lot of discontent.”

The lack of power is an economic drain on the state, according to Fayaz Ahmad Punjabi, junior vice president of the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “Electricity is like food for industry, it’s a necessity,” he said. “But in Kashmir today, it’s a luxury. So industry suffers, people suffer. Power is life, and we don’t have enough of it.”

Modi’s Pledge

Modi pledged to bring power to 18,452 unelectrified villages within 1,000 days in his August 2015 Independence Day national address. As of Oct. 31, electricity had reached 15,218 or 82 percent of those villages. In Jammu and Kashmir, 100 out of 134 villages, encompassing 270,000 households, lacking electricity were still waiting to be connected.

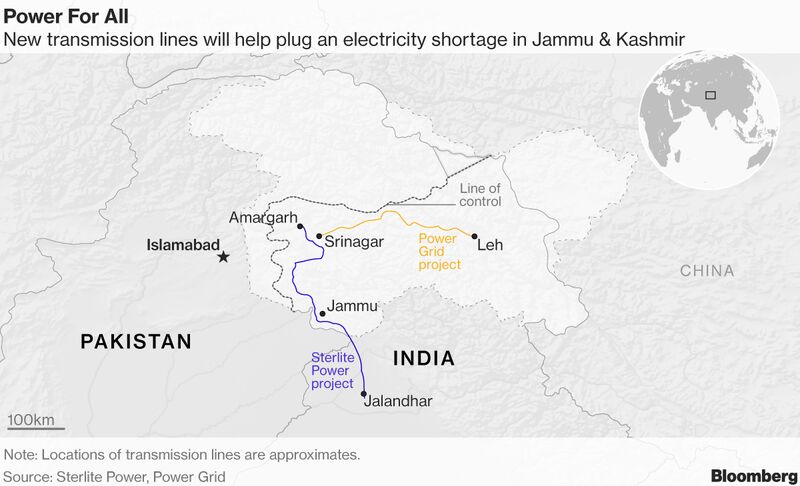

The government is trying to speed up progress with two transmission-line projects.

The Sterlite project will bring power from Jalandhar, in northern Punjab state, to Amargarh, near Srinagar, along a 441-kilometer line running parallel to the so-called Line of Control that marks part of India’s de facto northern border with Pakistan.

The project, which will cost more than 26 billion rupees, is almost finished and Sterlite aims to start supplying as much as 1,000 megawatts to the power-starved valley in late December, several months ahead of schedule.

A dearth of suitable roads in some remote areas meant dozens of mules were used to haul construction material and Sterlite hired an air crane from Erickson Inc. to lift pieces for transmission towers to peaks as high as 3.8 kilometer (12,500 feet) in the Pir Panjal Range.

“We got incredible support from the state government,” said Agarwal, Sterlite’s CEO. “We’ve been working relentlessly despite the curfews, despite the unrest in Kashmir.”

Winter Freeze

A second project managed by state-owned Power Grid Corp. will run electricity 350 kilometers from Srinagar to the Ladakh region in the state’s northeast, bordering China.

“Kashmir and Ladakh freeze in winter,” said Nirmal Kumar Singh, Jammu & Kashmir’s deputy chief minister, in an interview. “Transmission is a big hurdle.”

The state’s peak power demand is about 2,700 megawatts, though it gets merely 2,100 megawatts — about 1,100 megawatts from hydro electricity produced within the state and the rest from other states through an existing Power Grid transmission line. A lack of transmission capacity prevents it bringing in more.

Dark Winters

Ladakh, a desert region with about 300,000 people between the Himalayan and Karakoram mountains, gets only about 25 megawatts of hydroelectricity in summer. In winter, it plunges into darkness, save a couple of hours each day when army-supplied, diesel-powered generators run.

Power Grid’s line will cost 22 billion rupees and carry as much as 150 megawatts of electricity over mountains 4.6 kilometers above sea level when it’s completed in 2018.

“Our line passes through Drass, one of the coldest and highest inhabited places,” said Anil Jain, an executive director with Power Grid, who anticipates electricity demand in Ladakh will boom once homes and businesses are connected to the grid.

Providing power shows that the government in New Delhi is eager to develop the state and support the local economy, but more work is needed to resolve long-standing grievances, including a resumption of talks between India and Pakistan to settle a territorial dispute over Kashmir, said Zahid Shahab Ahmed, a research fellow at Deakin University in Melbourne, who focuses on peace and security in the Muslim world.

‘Deep Wounds’

“Deep wounds cannot just be healed by the constant supply of electricity,” Ahmed said. “The people of Jammu & Kashmir need other freedoms, including security of their lives.”

The power projects may be helping on that front, too, by forging a more conciliatory and collaborative approach.

After Sterlite faced initial resistance from locals, it suspected that state-sponsored protection could make it more vulnerable to attack and found it could better manage security using a private company staffed by mostly locals.

Linking the remote Himalayan region to the national power grid symbolizes a commitment to strengthen ties with the country’s farthest state, said Baba at the Central University of Kashmir.

“The central government’s push to increase power supplies is an important indicator that it’s serious about bringing the state back into the national mainstream,” he said.