The latest trigger for trouble in Jammu & Kashmir involves the Centre’s questioning of a special privilege, accorded to the state by the Indian Constitution. Any misstep with regard to it has the potential to cause an explosion in the valley, already fraught after months of unrest.

Recently, a Kashmiri woman called Charu Wali Khan, settled outside the state, challenged the legality of Article 35A of the Indian Constitution that allows J&K to define its “permanent residents”. She claimed in her petition to the Supreme Court that such a law takes her succession rights away and disenfranchises her.

In its response, the court sent notices to the Centre and the state governments last month to address her plea, following which Advocate General K Venugopal told the bench of Chief Justice JS Khehar and Justice DY Chandrachud that Article 35A raises several “sensitive questions” so the point about its legality demands a “larger debate”. The court then referred the case to a three-judge bench and set a six-week deadline for a final verdict.

In the mean time, political sentiments in the state are in a turmoil. The possibility of the Centre tampering with Article 35A has united the ruling PDP and Opposition, both defending the hurt sentiments of ordinary Kashmiris.

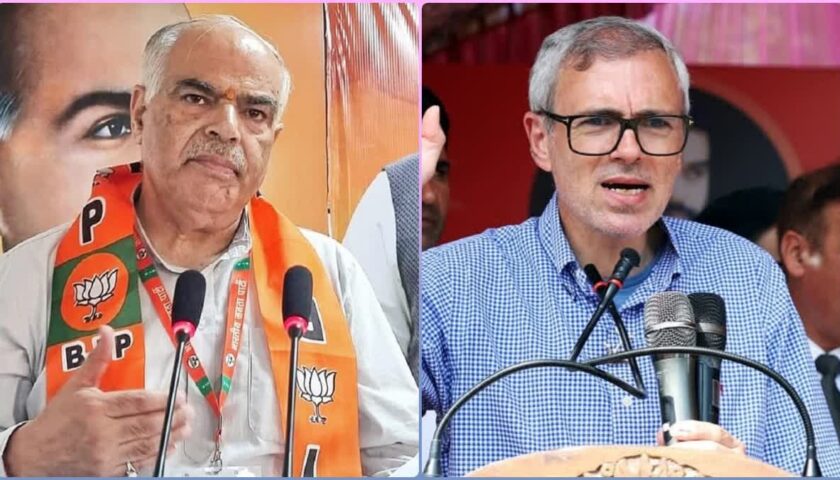

Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti has warned, in well-chosen words, that no one will be left in the state to hold the national flag if Article 35A is tinkered with. National Conference leader Omar Abdullah has also added his voice to the controversy, saying that questioning the validity of Article 35A would be as good as challenging the accession of J&K.

In spite of the political rhetoric, there is more than a grain of truth in these apprehensions. Any alteration to Article 35A may leave the government at the Centre with a hot mess in its hands, damaging the vestiges of goodwill that ordinary Kashmiris may still have towards the Union of India. Here’s why.

Article 35A was added through the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954, issued under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which grants special autonomy to the state of J&K. The J&K Constitution (J&K is the only state allowed to have its separate Constitution) was adopted on 17 November 1956. It defined a permanent resident as someone who was a state subject on 14 May 1954, or has been a resident of the state for 10 years, and has lawfully acquired immovable property in the state.

This definition is seen as limiting by several parties and pressure groups, especially the BJP and the RSS. Over the years, workers of these organisations, among others, have lobbied for the repeal of Article 35A. The BJP manifesto for the J&K assembly polls, for instance, as The Indian Express pointed out, promised “land at cheap rates for establishment of Sainik colonies in major towns” for retired soldiers.

According to the opponents, the conception of a permanent resident, derived from Article 35A, is chiefly responsible for the predominance of Muslims in the valley. Should the executive write it down, the move would then usher in a demographic change in J&K, with new settlers going there to live.

In 2014, an NGO had filed a writ petition seeking to strike Article 35A down, but the case is pending in the Supreme Court. The J&K state government has filed a counter-affidavit asking for the plea to be dismissed, though the Centre has not obliged yet.

Politicians like Abdullah emphasise that Article 35A is “an article of faith”, the breach of which could have far-reaching repercussions, worse than the months of unrest unleashed by the Amarnath land row in 2008. Whereas historians like Srinath Raghavan have a more nuanced take on the same point.

Writing recently in the Hindustan Times, Raghavan clarified the exact terms of J&K’s autonomy, which gives Article 35A its legitimacy. The relevant section is worth quoting in full.

The legality of Article 35A is being challenged on the grounds that it was not added to the constitution by a constitutional amendment under Article 368. This is a specious argument. For the article does not by itself confer any right on J&K state subjects. The Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja of Kashmir in October 1947 specified only three subjects for accession: foreign affairs, defence and communications. In July 1949, Sheikh Abdullah and three colleagues joined the Indian Constituent Assembly and negotiated over the next five months the future relationship of Kashmir with India.

This led to the adoption of Article 370, which restricted the Union’s legislative power over Kashmir to the three subjects in the Instrument of Accession. To extend other provisions of the Indian Constitution, the Union government would have to issue a Presidential Order to which state government’s prior concurrence was necessary. Further, this concurrence would have to be upheld by the constituent assembly of Kashmir, so that the provisions would be reflected in the state’s constitution. This implied that once Kashmir’s constituent assembly framed the state’s constitution and dissolved, there could be no further extension of the Union’s legislative power. This was the core of J&K’s autonomy.

Any attempt to undermine, or dilute, these principles, already enshrined in the Constitution and wrenched after many decades of violence and bloodshed, can only serve to perpetuate the current cycle of unrest. In any case, it won’t act as a deterrent to terrorism in the valley. As Mufti tellingly said to the government at the Centre, “By [challenging Article 35A], you are not targeting the separatists. Their agenda is different and it is totally secessionist.”

Kashmir has been on the boil since last July, after Hizbul Mujahideen leader Burhan Wani was killed by the Indian Army. Since then, hundreds of ordinary people have been injured or killed in clashes with the armed forces and regular Internet shutdown has crippled normal life in the state. Taking a hasty step to deal with Article 35A under such dire circumstances, out of purely jingoistic or ideological concerns, may prove to be the last straw in the Centre’s relationship with the state.