Images of students confronting police on campuses have come to symbolise Kashmiri protests against Indian rule as much as gun-toting militants in fatigues, in what security officials and separatist leaders say is a dangerous new phase of the conflict.

Images of students confronting police on campuses have come to symbolise Kashmiri protests against Indian rule as much as gun-toting militants in fatigues, in what security officials and separatist leaders say is a dangerous new phase of the conflict.

The sharp rise in violence in recent weeks is more spontaneous than before, complicating the task of Indian security forces trained largely in counter-insurgency and poorly equipped to contain broader unrest.

A political stalemate in India’s only Muslim-majority state is a further hurdle to resolving the long-running Kashmir dispute, as is rising Hindu nationalism in some parts of India since Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014.

“We can ensure that militant numbers remain relatively low and we have stopped the weapons flow. The bigger challenge is how to control protesters, how to engage with them,” said one senior army official, who asked not to be named because he was not authorised to speak to media.

When security forces entered a college last month in Pulwama, 30 km (19 miles) south of Kashmir’s summer capital of Srinagar, hundreds of students threw stones at their vehicles before fighting pitched battles inside college corridors and bathrooms.

Within days, widespread protests forced most colleges and secondary schools in Indian-controlled Kashmir to close. Teenaged girls took to the streets for the first time in years. At least 100 protesters were wounded.

“Every student is trying to say that we … want nothing to do with India,” a 19-year-old protester said in the backroom of a Pulwama restaurant, as security forces clashed with locals on the outskirts of town.

He asked not to be named because his father was a policeman.

A local police chief said security forces were steering clear of campuses to avoid provoking more violence.

Police were appealing to parents to ensure children “do not indulge” in violence, Kashmir inspector general of police S.J.M. Gillani said, adding that most areas were back under control.

Unrest has simmered in Kashmir, home to a separatist movement for decades, since last July, when a popular militant leader was killed, sparking months of clashes that left more than 90 civilians dead.

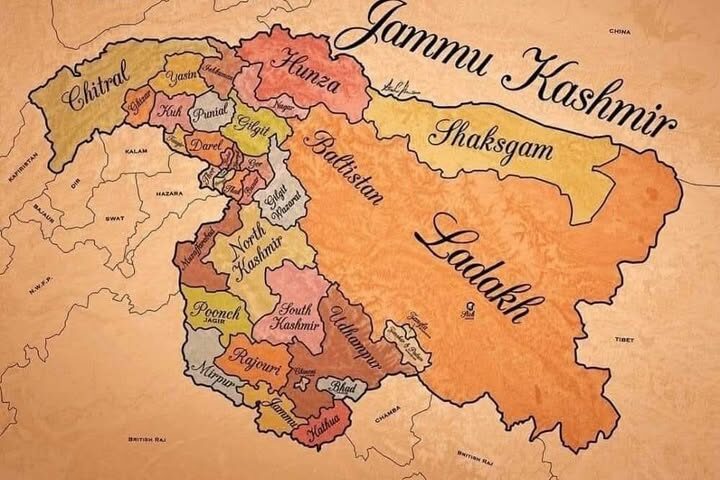

One of the world’s oldest conflicts, Kashmir’s troubles began when the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was divided in 1947 between India and Pakistan, nuclear-armed rivals who fought two of three wars over the region.

An insurgency that erupted in 1989 against India has eased in recent years, but most Kashmiris yearn for independence, accuse security forces of widespread rights abuses and some support the few hundred militants still fighting.

Delhi Demands End To Violence

Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, leader of a moderate Kashmiri separatist faction, said protesters were for the first time ignoring calls to stop.

“Today there is absolute hate for India. They don’t listen to anyone,” he told Reuters in Srinagar.

India’s former spy chief, A.S. Dulat, said the Kashmir situation “has never been so bad”.

Still, New Delhi has stuck to its tough line, demanding an end to violence before talking with separatists.

“All these activities of stone pelting have to stop. Then will the government consider talking,” said K.S. Dhatwalia, a home ministry spokesman.

Politicians also say that, in contrast to earlier unrest, there is no obvious leader to negotiate with.

Previous waves of violence in 2008 and 2010 fizzled out after a year or so as local people tired of shutdowns. There is little sign the current protests will end soon, however.

In villages set amid the mustard fields and apple orchards of Kashmir Valley, people openly praise militants and protesters. Locals complain of more police checkpoints, while grieving mothers show photos of loved ones killed in the unrest.

Politicians in southern districts have left home for the relative safety of Srinagar. Suspected militants shot dead Abdul Gani Dar, Pulwama district president for the ruling party, in April, one of a spate of attacks on mainstream politicians.

Support for violence has expanded to central parts of the state, traditionally the most peaceful.

March saw the first large-scale violence in the town of Chadoora since the early 2000s, and three civilians were killed. Fresh graffiti praising militants and telling “Indian Dogs” to “Go back” dot the town centre.

“India Losing Kashmir”

Shabir Ahmad, a doctor, said he began supporting militants and protesters after his brother-in-law, 21, was shot dead in Chadoora amid a stand-off with security forces.

“India is losing Kashmir because of its own doing,” the 35-year-old said at his family home, sitting next to his grieving mother-in-law.

Some Kashmiris warn that rising nationalist sentiment across parts of India, led by Modi’s hardline Hindu supporters, is deepening their sense of estrangement.

Modi last month asked Kashmiri youngsters to choose between “tourism and terrorism”, comments that angered locals.

Several Kashmiris living in ‘mainland’ India have returned home after facing discrimination, including student Hashim Sofi, 27, who arrived at his hostel room in Rajasthan state to a T-shirt with “Kashmiri dog” scribbled on the front.

“They are saying that all Kashmiris are terrorists,” he said by telephone.

A series of attacks against Muslims accused of slaughtering cows, an animal sacred to Hindus, has increased worries among Muslims.

Waheed-ur-Rehman Parra, an aide to Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, who governs in an alliance with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, said he remained hopeful that Delhi would launch a new dialogue.

“Kashmir cannot be seen as an isolated place,” he said. “Indian politics are becoming more polarised.”