Nepotism in Kashmir Politics: Impact of 2nd & 3rd Generation Dynasties | Public Trust & Power Dynamics

By: Javid Amin | 05 January 2025

When Politics Becomes Inheritance

In Jammu and Kashmir, politics is not simply a career path — it is often an extension of family heritage. Over decades, 2nd- and 3rd-generation leaders have consolidated influence across party structures and electoral landscapes. For many ordinary Kashmiris, this has created a perception that access to power is inherited rather than earned.

While dynastic continuity is defended by some as stability and political experience, growing sections of society — especially youth — argue it amounts to political gatekeeping, reducing citizen participation to followers of family brands rather than independent leaders.

This report synthesizes on-ground feedback, documented history, electoral context, and expert viewpoints to examine what dynastic concentration means for governance and democracy in Kashmir today.

Kashmir’s Political Dynasties: The 2nd & 3rd-Generation Landscape

Prominent Family-Centred Lineages

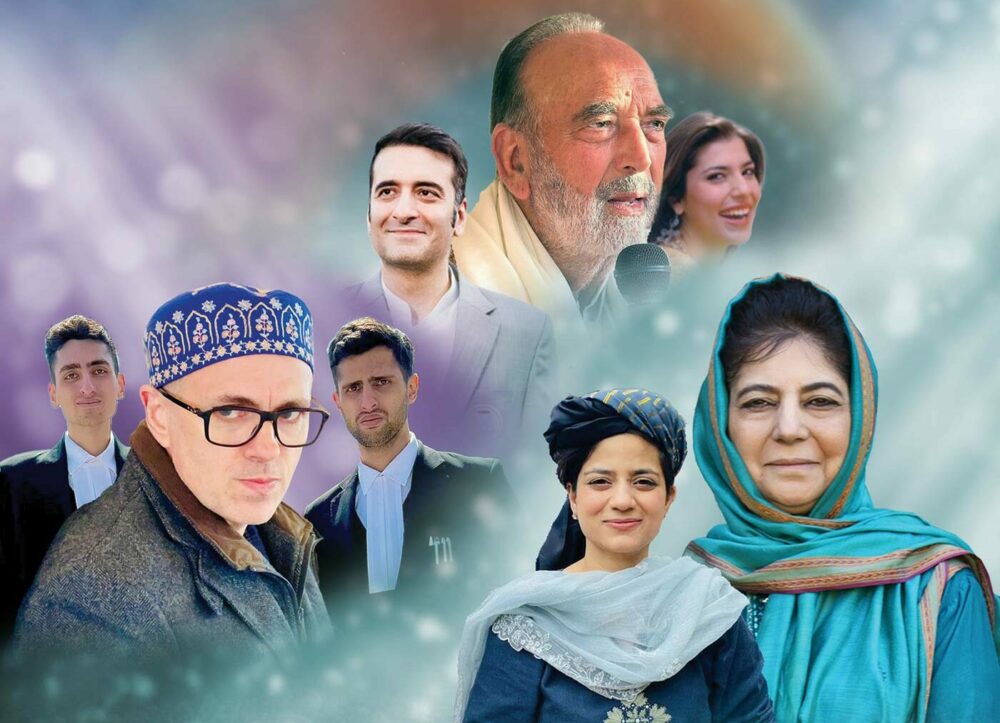

The most visible dynastic political blocs continue to shape party direction and leadership succession:

1. The Abdullah Family — National Conference (NC)

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah → Dr. Farooq Abdullah → Omar Abdullah

A cornerstone of mainstream Kashmiri politics, the Abdullahs represent the most established political dynasty, with generational continuity embedded in the NC’s identity.

2. The Mufti / Sayeed Family — People’s Democratic Party (PDP)

Mufti Mohammad Sayeed → Mehbooba Mufti → Iltija Mufti

Iltija’s increasing political visibility reflects PDP’s sustained family-led leadership structure.

3. The Lone Family — People’s Conference (PC)

Abdul Gani Lone → Sajjad Lone / Bilal Lone

Once defined by separatist-mainstream intersections, the Lone family today holds considerable political bargaining relevance.

4. The Sagar Line — National Conference

Ali Mohammad Sagar → Salman Sagar

Symbolic of party-driven political inheritance within mainstream structures.

5. The Larvi / Ganderbal Sufi-Political Line

Mian Bashir Ahmed → Mian Altaf Ahmad Larvi

Demonstrating the persistence of hereditary authority rooted in religious-political influence.

Fact Box — Major Dynastic Lines in J&K Politics

| Family / Lineage | Political Party | Generations Active | Key Known Members |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdullah | National Conference (NC) | 3 (major) + emerging | Sheikh Abdullah, Farooq, Omar |

| Mufti/Sayeed | Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) | 2 (major) + emerging | Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, Mehbooba, Iltija |

| Lone | People’s Conference | 2 | Abdul Gani Lone, Sajjad Lone |

| Sagar | National Conference | 2 | Ali Mohammad Sagar, Salman Sagar |

| Larvi | National Conference | 2 | Mian Bashir Ahmed, Mian Altaf Ahmed Larvi |

| Aga Family | PDP | Emerging | Aga Syed Muntazir Mehdi |

Why Nepotism Persists: Structural Anchors of Power

1. Brand Loyalty and Historical Reverence

Longstanding political families like the Abdullahs and Muftis enjoy brand recognition across generations, supported by historical legacy and emotional narrative about Kashmir’s past struggles. This often translates into blanket voter loyalty that eclipses newer, merit-based entrants. The New Indian Express

2. Candidate Vetting and Party Machinery

Political parties in J&K often award tickets to familiar family names, believing they bring with them campaign resources, recognisability, and electoral reliability. The result is closed candidate selection, limiting the rise of grassroots leaders.

3. Mentorship or Monopoly?

While some view succession as mentor-protégé progression, critics argue that it functions as a gatekeeping mechanism, with internal party democracy frequently sidelined in favor of lineage continuity.

Ground Voices: Public Sentiment on Dynastic Politics

Conversations with residents in central and south Kashmir reveal a broad spectrum of attitudes, shaped by personal experience, economic conditions, and political context:

A. Respect with Reservations

Some older voters, recalling the historical leadership roles of families like the Abdullahs, express respect for continuity, associating certain names with resistance and identity history.

However, this respect is now tempered by criticism that past heroism does not justify automatic succession today — especially when performance seems disconnected from current public needs.

B. Youth Frustration and Disillusionment

Young professionals and students repeatedly articulate a similar theme:

“Why does it always start with a surname? We have ideas, education, energy — but not names.” (Response from a Srinagar graduate)

Many feel that opportunities for political contribution outside family circles remain limited, fostering apathy or alienation.

C. Voter Fatigue and Cynicism

Some voters describe choices between dynasty candidates as “semi-symbolic” — meaning, voters feel they are choosing between brands rather than performance-driven leadership.

How Nepotism Shapes Governance and Accountability

1. Policy Priorities vs Party Loyalty

Heavy dynastic influence can skew governance toward preserving party legacy and personal networks rather than innovating on urgent public issues like unemployment, health services, or local development.

2. Electoral Competition and Merit Barriers

Candidates outside influential families often struggle to secure funding, visibility, or organizational backing — even when they have strong local credentials. This reinforces patronage over performance.

Emergent Alternatives and Shifting Dynamics

Despite entrenched patterns, several counter-currents indicate possible change:

1. Independent and Youth Voices

A noticeable number of independent candidates and youth activist groups contest elections and social platforms, advocating merit over inheritance and accountability in governance.

2. Internal Party Reform Debates

Discussions within parties about promoting internal primaries, merit-based candidate selection, and transparency are emerging, especially among younger party workers.

3. Media Amplification of Nepotism Concerns

Local media have increasingly spotlighted dynastic succession as public policy concern, catalyzing discussion beyond elite corridors.

Fact Panel — Dynastic Representation Metrics

| Metric | Estimate |

|---|---|

| MLAs from known political families (approx.) | 10–15 (out of J&K Assembly seats) |

| Major parties with generational leaders | 3+ |

| Voter sentiment polling on dynasty concerns | Growing over recent years (anecdotal) |

Public Trust and Democratic Implications

Nepotism in politics carries broader democratic consequences:

-

Limits meritocratic entry into leadership roles

-

Sustains elite networks rather than grassroots accountability

-

Deepens cynicism among voters, especially youth

-

Erodes institutional trust over time

While legacy can sustain institutional memory, dominance without openness often undermines citizen confidence.

Challenges Ahead

Despite voices for change, entrenched networks remain strong due to:

-

established voter loyalty patterns

-

centralized party control over nominations

-

resource advantages of political families

-

media cycles that focus on personalities over policies

Reforming this requires structural interventions — not mere rhetoric.

Editorial Takeaway: Revisiting Nepotism Without Rejecting History

Nepotism in Kashmir’s political landscape is neither isolated nor accidental. It is tied to historical legacies, party structures, and social perceptions that grew over decades. However, what once may have been legitimate leadership succession now often feels like limited political mobility for those outside established families.

For democracy to deepen:

-

politics must be more inclusive

-

parties must embrace internal transparency

-

voters must evaluate performance, not just lineage

Kashmir’s aspirations — economic, cultural, democratic — demand representational diversity, not just repeated family names.

Because leadership legitimacy should not be inherited — it should be earned.

Quick Take:

Nepotism in Kashmir politics — driven by 2nd- and 3rd-generation dynasties and leader-centric networks — continues to shape power structures and limit political mobility. Families like the Abdullahs, Muftis and Lones dominate leadership space, while parties such as DPAP and BJP remain command-controlled. The result: constrained opportunity for new voices, youth frustration, and slower governance innovation — alongside rising public demand for transparency and reform.