Post-Article 370 Land Transactions: Jammu Leads in Non-Resident Allotments, Kashmir Trails

By: Javid Amin | 31 October 2025

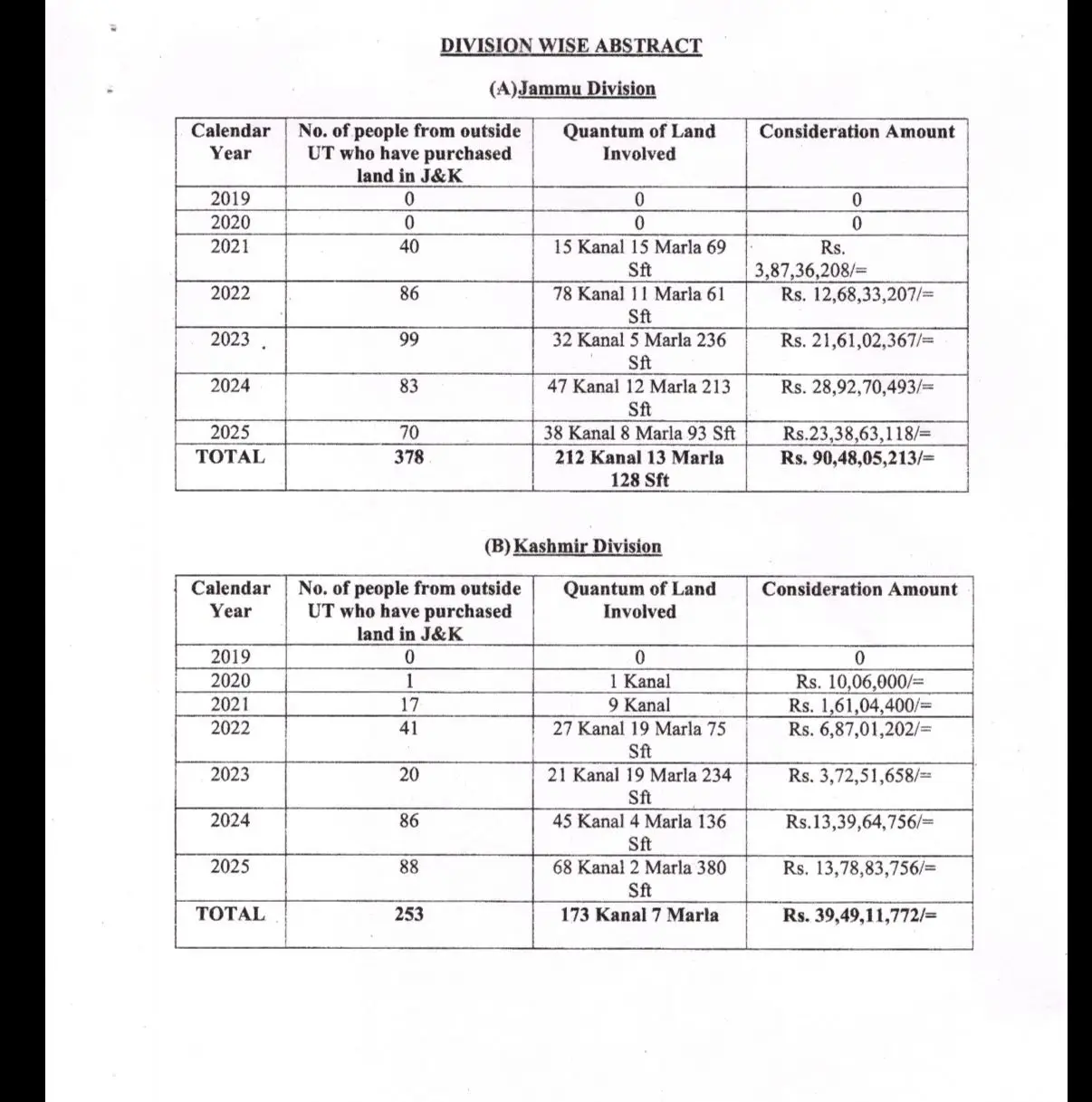

In a significant shift in land-ownership patterns in the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), government data shows that 631 non-residents—i.e., persons not originally domiciled in J&K—have acquired land totaling over ₹130 crore since the abrogation of Article 370 and the region’s re-organisation in 2019.

Of this figure, 378 non-residents purchased land in the Jammu region (212 kanal, 13 marla, 128 sq ft; valued at ~₹90.48 crore), and 253 non-residents in the Kashmir region (173 kanal, 7 marla; valued at ~₹39.49 crore).

Why does this matter? For decades, land-ownership and property rights in J&K were tightly controlled under the special constitutional status conferred by Article 370/35A. With their removal and the re-organisation of the region, long-standing guardians of local land rights, regional identity and demographic balance are now faced with fresh realities. This article delves into the figures, policy shifts, regional breakdowns, political and social implications, investor motivations, and what this could mean for the future.

Background: From Special Status to Open Ownership

The Legal Landscape Prior to 2019

Under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, the erstwhile State of Jammu & Kashmir enjoyed a “special status”. Wikipedia+1 The companion provision, Article 35A, empowered the J&K legislature to define “permanent residents” of the state and to grant them exclusive rights to own land, immovable property, vote, access state jobs, etc.

In practical terms, this meant non-residents from other Indian states were barred from owning land in J&K. The policy was framed to protect local demographic, economic and cultural interests. Economists and political scientists have long noted that land in J&K was not a mere commodity, but intimately tied to identity, economy, security and region-specific tensions.

The Turning Point: August 5, 2019 and its Aftermath

On 5 August 2019, the Government of India announced the removal of Article 370 and related provisions, thereby ending J&K’s special status. The subsequent Jammu & Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 (effective 31 October 2019) bifurcated the state into two union territories: J&K, and Ladakh.

With this constitutional overhaul, the protective walls around land-ownership were lowered. Rules which had hitherto prevented non-locals from buying property were altered or repealed, opening up J&K’s land market to outsiders. The significance was profound: a region long governed by war, exclusion, and “permanent residents” definitions would now join “open market” dynamics that typically govern India’s land economy.

Policy Shift: What changed on the ground

With the special status removed, two major shifts occurred:

-

Land Ownership Relaxed: Non-residents could now purchase land in J&K (subject to rules, approvals and local processes).

-

Lease & Grant Regime Altered: The government signalled reforms in land-grants, leases and renewals—particularly under the Jammu & Kashmir Land Grants Rules, 2022.

The upshot: The legal regime tilts from “protection of local land-rights” to “liberalised investment plus regulation”. That design-change sets the scene for the data we see today.

The Numbers: Land Allotted to Non-Residents (2019-2025)

Let’s break down the government-disclosed figures in detail. The following numbers derive from the written reply by the Revenue Department to an Unstarred Question (No. 286) tabled by MLA Sheikh Ahsan Ahmed in the J&K Legislative Assembly.

Aggregates

-

Number of non-residents who have acquired land: 631.

-

Approximate total value of land: ₹129.97 crore (rounded to “over ₹130 crore” in some reports).

-

Total area acquired: Over 386 kanals plus 128 sq ft (when combining Jammu + Kashmir divisions) according to one report.

Regional Breakdown

Jammu Division

-

Buyers: 378 non-residents.

-

Area: 212 kanal, 13 marla, 128 sq ft.

-

Value: ₹90.48 crore.

Kashmir Division

-

Buyers: 253 non-residents.

-

Area: 173 kanal, 7 marla.

-

Value: ₹39.49 crore.

Year-by-year trend

According to The New Indian Express:

-

In 2020: 1 non-resident purchased 1 kanal worth ~₹10.06 lakh.

-

2021: 57 non-residents purchased 24 kanal, 15 marla, 69 sq ft worth ~₹5.48 crore.

-

2022: 127 outsiders bought 106 kanal, 10 marla, 136 sq ft worth ~₹19.55 crore.

-

2023: 119 non-residents bought 54 kanal, 5 marla, 72 sq ft worth ~₹25.33 crore.

-

2024: 169 non-residents acquired 92 kanal, 17 marla, 77 sq ft worth ~₹42.32 crore.

-

2025 (so far): 158 outsiders bought 106 kanal, 11 marla, 201 sq ft worth ~₹37.17 crore.

Usage Clarification

The government has explicitly stated that no land has been allotted to non-residents for the construction of shopping malls, hospitals or colleges since 2019.

However, it has not provided a detailed breakdown of exactly what the purchased land is being used for (residential, commercial, investment) or full geographic distribution beyond the broad Jammu/Kashmir division split.

Interpreting the Data: What Does It Really Show?

Investment vs. Settlement: Understanding the Motives

When outsiders acquire land in a region previously inaccessible to non-locals, motivations tend to fall into three broad categories:

-

Residential – Personal Use: Buying a home, holiday residence, or relocation.

-

Commercial/Investment: Purchasing land as an asset, to develop or resell.

-

Speculative / Strategic: Acquiring land for future value, real-estate play, or institutional/industrial use.

The data from J&K suggests a strong tilt toward investment/speculation, given the fairly modest land-areas per buyer and the jump in value especially in recent years. The government’s own statement that none of the allotments were for large institutional purposes (malls, hospitals, colleges) reinforces the notion of smaller-scale purchases.

Regional Disparities: Jammu vs. Kashmir

The Jammu division accounts for about 70% of the total value (₹90.48 crore out of ~₹130 crore) despite fewer kanals in absolute terms than may be expected. This suggests either higher land-price per unit in Jammu, or more premium locations being bought. The Kashmir division lags in value though still significant (~₹39.49 crore) for 173 kanal.

Reasons for these regional differences may include:

-

Land-price variation: Jammu may have seen higher valuations, or better accessibility for non-residents.

-

Infrastructure & connectivity: Jammu’s relative ease of access from other Indian states may make it more attractive for outsiders.

-

Administrative/regulatory differences: Local norms, approvals, or lease-/grant-structures could differ between Jammu and Kashmir divisions.

-

Security/context issues: The Kashmir Valley has historically faced greater security and regulatory oversight which might dampen outsider purchases.

Trend of Growth: A Rising Curve

From data year-by-year, the trend is upward: from single kanals in 2020 to over 100 kanals in 2025 so far. The value also climbs, notably from ~₹5.48 crore in 2021 to ~₹42.32 crore in 2024 in that one year alone. This shows not only more buyers but more valuable purchases.

If the trend continues, by the end of 2025 we might see the value significantly above ₹150 crore and land area well beyond 400 kanals.

Policy Signal: Land-Ownership Liberalisation

This data is a direct by-product of the post-2019 liberalisation of land-ownership rules in J&K. With the removal of permanent-resident restrictions, outsiders now have a legal pathway into what was once an exclusive land economy. In that sense, the numbers reflect not just market demand but policy enablement.

The Stakes: Why This Shift Matters

Demographic & Cultural Implications

Land in J&K is not just a commodity; it is deeply tied to identity, community, culture and politics. The legacy exclusion of non-residents was meant to safeguard local demographics. With that guardrail removed, outsiders purchasing land may:

-

Change local access and ownership dynamics of land-resources.

-

Create perceptions (and possibly realities) of demographic dilution or shift.

-

Stimulate tensions around region, community, and who “belongs” to the land.

Political and Security Concerns

J&K has long been a region of contestation—territorial, political and ideological. Changes in land-ownership can become triggers for insecurity or politicised debate:

-

Critics may argue that large purchases by non-locals risk eroding local control and undermine the promise of autonomy.

-

Supporters will argue it opens up the region to investment, jobs, development and integration into the national economy.

-

Security analysts will ask: are these purchases being monitored for strategic or undesirable influence?

-

Locals may feel marginalised if land becomes inaccessible, unevenly priced or appropriated by outsiders.

Economic and Developmental Dimensions

From an economic standpoint, opening land-markets to non-residents can drive:

-

Increased capital inflows, potentially boosting construction, infrastructure, hospitality, tourism.

-

Raising of land-prices, which may benefit existing land-holders but also raise cost of living, housing affordability for locals.

-

Diversification of ownership and potential new business entrants which may stimulate jobs and entrepreneurship—but may also crowd out traditional local participants.

Governance & Transparency Imperatives

The shift demands robust governance frameworks:

-

Are all purchases compliant, with local due-diligence, transparent approvals and tax/levy compliance?

-

Is there parity in how rules are applied across Jammu and Kashmir divisions? Indeed, critics already allege bias. Kashmir Life

-

Is there oversight of “end-use” of land (residential vs commercial) to prevent misuse, speculation bubbles or unauthorised developments?

-

Are local residents’ interests protected—especially in regions with high social, cultural or security sensitivity?

Voices From the Ground: Local Reactions & Concerns

While official data gives us a macro view, the human dimension reveals worry, hope and complexity.

Local Land-Owners’ Perspective

For many local residents, the opening up of land-ownership to outsiders is a mixed blessing:

-

Some welcome the rise in land-values; those who already own property may see it as asset appreciation.

-

Others worry that outsiders will out-bid locals, making housing and land less affordable for native residents and families.

-

Long-time inhabitants fear loss of community control, especially in rural or semi-urban zones where land has been held within families for generations.

Political Opposition Voices

For example, in the J&K Legislative Assembly, NC legislator Tanvir Sadiq has alleged regional bias in implementing land-grant rules:

“Denying renewals and pushing properties to auction doesn’t empower—it uproots Kashmiri entrepreneurs and benefits outsiders.” Kashmir Life

He makes two key points:

-

Local businesses (especially small-hotels, shops, cooperative societies) feel threatened by changing land regime.

-

There is concern about uneven enforcement of rules: what’s allowed in Jammu may be harder in Kashmir; locals fear losing control.

Investor / Non-Resident Viewpoint

Although individual non-resident buyers are not widely quoted in press, some likely motivations emerge:

-

Seeing J&K as “virgin frontier” real-estate market now accessible; tourism/policy reforms may have unlocked latent potential.

-

Buyers may be looking for holiday homes, second residences, or speculative assets with the hope of appreciation.

-

Commercial players may eye hospitality, environmental/regional tourism and allied services—though the government clarifies no large grants (malls/hospitals/colleges) yet allotted to outsiders.

Potential Impact on Local Communities

The overall picture emerging: A region in transition. On the one hand, fresh flows of capital, potential infrastructure development and national integration; on the other, fears of displacement, local marginalisation and erosion of traditional land-rights.

Policy & Regulatory Issues: Nuts and Bolts

The Jammu & Kashmir Land Grants Rules, 2022

One of the key regulatory shifts post-2019 is the Land Grants Rules (2022) which govern leases, grants, renewals and auctions of land. For example, in Jammu division:

“Under the J&K Land Grants Rules, 2022 (SO 658), all leases—except residential ones—granted under earlier land grant rules will not be renewed. Instead, such expired or determined leases will be put to open auction.” The News Now+1

This policy indicates a move toward transparency and market-based renewal, but it also raises questions:

-

Are local small-enterprises (shops, hotels) losing out if they cannot compete in auctions?

-

How will this affect legacy lease-holders who expected automatic renewal under older rules?

-

Will auctions favour large players who may be outsiders, thereby shifting ownership further away from locals?

Monitoring and Use-Case Reporting

While the government reports the quantity and value of land purchases by non-residents, it has not yet published detailed data on:

-

What percentage of land is for residential vs commercial vs mixed use.

-

Geographic spread by district, village or neighbourhood (rather than just Jammu vs Kashmir).

-

Buyer-profiles: from which states, what social-economic backgrounds, how many corporate entities.

-

Post-purchase outcomes: development, resale, whether the land remains idle.

The absence of such granularity means policy watchers and civil society face a transparency gap.

Implementation Uniformity & Regional Differences

As noted earlier, legislators and local actors have flagged potentially uneven rule-application between Jammu and Kashmir. The concern is that while outsiders may find it relatively easier to transact in certain zones (especially Jammu), the process in Kashmir may be more cumbersome, reinforcing the sense of regional disparity.

Ensuring uniform application of land-laws, equal access to transaction systems and protections for local small-holders is crucial for legitimacy.

What’s Next: Risks, Opportunities & Scenarios

Investment Potential & Development Upside

Opening up land-ownership to non-residents can drive positive outcomes:

-

Tourism boost: J&K has natural beauty, climate, heritage—outsider investment could upscale hospitality, second-homes, eco-resorts.

-

Infrastructure growth: Increased land transactions may trigger demand for roads, utilities, value-added services (retail, serviced housing).

-

Job creation: New developments, construction, services may generate employment, especially if locals are integrated.

-

Asset appreciation: For both locals and outsiders, the open land-market may raise asset values, increasing wealth-effect.

Risks & Unintended Consequences

However, the flip side contains significant risks:

-

Affordability crisis: If land and housing prices rise steeply, local residents (especially low- and middle-income) could be priced out.

-

Speculation & idle-land: Outsiders may buy land simply to hold, not develop—leading to land-lying idle, local opportunity costs.

-

Displacement of local businesses: Legacy lease-holders, shops, small hotels may face auctions they cannot afford, losing rights.

-

Demographic and identity tensions: When outsiders own large tracts, locals may feel marginalised or culturally diluted, fuelling unrest.

-

Oversight/lemons problem: If regulation/enforcement weak, land-deals could include misuse, fraud, encroachment—historical precedents in J&K remind us of this. For instance, the controversial Roshni Act land-grant scheme of the early 2000s highlighted how land-allocation without transparency can create large losses and inequity.

Scenarios Looking Forward

-

Controlled Growth Scenario: The government safeguards local-resident rights, deploys transparent auction rules, monitors land-use, channels outsider-investment to required infrastructure. Outcome: Balanced development, local gains + outsider capital.

-

Speculation Boom Scenario: Rapid land-buying by outsiders drives prices up, locals get sidelined, many lands lie idle, local resentment grows—they feel “outsiders are gobbling up our land”. Outcome: socio-political tensions, regulatory backlash.

-

Regulatory Backlash Scenario: Due to perceived harms, government imposes stricter rules, limitations, caps on outsider purchases—effectively reversing or slowing liberalisation. Outcome: slowdown in investment, but potential relief for locals.

Regional Case Studies: What to Watch

Jammu Division: High Value, Growing Activity

With 378 non-resident buyers purchasing 212 kanal plus area, valued at ~₹90.48 crore, Jammu appears to be the hotspot for outsider interest. Key features:

-

Relatively better connectivity (roads, rail, airport) with rest of India.

-

Tourism access (e.g., Vaishno Devi, Jammu city) attracts investments.

-

Land markets likely better developed.

Watch-points:

-

Are local residents being included or excluded from equivalent land-opportunities?

-

Are land-prices skyrocketing, and what is the effect on rental/housing markets for locals?

-

What is the nature of non-resident buyers: local Indian states, NRIs, corporate?

Kashmir Division: Smaller Value, but Sensitive Context

With 253 non-residents acquiring 173 kanal, value ~₹39.49 crore, Kashmir presents a different dynamic:

-

The historical conflict zone and stricter security environment may limit outsider flows.

-

Local communities may feel more vulnerable to land-ownership shifts.

-

Land-price growth may be more muted—but also less accessible for locals.

Watch-points:

-

Which districts in Kashmir are seeing most outsider purchases? Urban Srinagar vs rural valleys?

-

What is the impact on local small enterprises tied to land (shops, hotels, households)?

-

Are regulatory approvals and monitoring more stringent—leading to a two-tier system between Jammu and Kashmir?

Strengths & Limitations of the Data

Strengths

-

Official government disclosure: The data comes via the Legislative Assembly reply.

-

Year-by-year breakdown data available (from The New Indian Express).

-

Regional differentiation (Jammu vs Kashmir) is provided.

Limitations

-

Lack of granular data: No district-wise, village-wise breakdown.

-

No data on buyer-profile: Where from, demographic/industry status.

-

No detailed usage information: residential vs commercial vs developed vs idle.

-

“Non-resident” is broadly defined; ambiguity remains around Indian citizens from other states, NRIs, companies.

-

Data stops at reported date; updates/ongoing transactions may lag.

-

Potential for under-reporting or mis-categorisation (e.g., cluster purchases, shell entities).

Given these, any analysis must be cautious and understand that while the broad trend is clear, the full picture has unresolved gaps.

Contextualising with Past Land-Scandals & Reforms in J&K

J&K has a complex history of land-allotments, state-grants and controversies. One of the most notable was the Roshni Act.

The Roshni Act: A Cautionary Tale

The Roshni Act (J&K State Land (Vesting of Ownership to Occupants) Act, 2001) was intended to vest occupancy rights for state lands in occupants in order to raise funds for power projects.

However, it became infamous for alleged misuse, corruption and the transfer of huge tracts of land at undervalue, prompting Supreme Court intervention and eventual repeal. Wikipedia

Lesson: Land-policy liberalisation without strong oversight, transparency and accountability can lead to systemic abuses.

Relevance to Current Situation

-

The 2019-onward liberalisation is large-scale: opening outsider purchases in sensitive region.

-

Controls and transparency matter: will the new wave replicate past mistakes or offer improved governance?

-

Local trust is at stake: Communities familiar with perceived land-grab histories may view new outsider purchases sceptically unless governance is rock solid.

Socio-Political Implications: Beyond the Numbers

Identity, Belonging & Local Trust

For decades, local residents of J&K have navigated identity questions: who is a “permanent resident”, who controls land, how do outsiders relate to local communities? With the reforms:

-

Outsider land-acquisition may be seen as challenge to local control.

-

Long-term residents may fear loss of community voice, especially in service-economy or tourism zones.

-

For young people in J&K seeking housing or starting businesses, rising land-costs may feel like exclusion rather than opportunity.

Political and Electoral Dimensions

In the run-up to future elections, these land reforms could become a flashpoint:

-

Local opposition parties may frame outsider land-ownership as a threat to regional integrity.

-

Government may argue liberalisation is necessary for development, jobs and national integration.

-

The balancing act will influence votes, local trust in institutions and governance.

Security and Strategic Dimensions

Land in hill-territories like J&K has strategic dimensions (border proximity, terrain control, access). Outsider purchases must be monitored for:

-

Compliance with land-use regulations (especially in security-sensitive zones).

-

Transparency regarding buyer identity and ultimate beneficiaries.

-

Ensuring no conflict with national security/regional autonomy considerations.

What Locals and Stakeholders Should Ask (and the Government Should Answer)

For Local Residents & Civil Society

-

What safeguards exist to ensure locals aren’t out-priced or displaced in land/housing markets?

-

What mechanisms permit small local businesses/lease-holders to access auctions or land-grant reforms fairly?

-

How will usage-monitoring happen (to ensure purchased land does not remain idle or tied up in speculation)?

-

Is there district-wise data available accessible to the public for transparency?

-

What support will be given to communities impacted by land-price spikes or outsider influx?

For the Government (UT Administration of J&K)

-

Publish a detailed breakdown: buyer-profiles, district/tehsil splits, usage of land (residential/commercial), conversion/development status.

-

Regularly update the numbers (ongoing 2025 onwards) so trends are visible in near-real time.

-

Ensure uniform enforcement of land-grant/lease renewal rules across Jammu and Kashmir divisions to avoid perception of bias.

-

Establish transparent auctions & grievance-redress in land-leases to protect legacy local holders.

-

Monitor land-use after acquisition: require that purchased land be developed or used within a defined timeframe, preventing speculative hoarding.

In Summary: The Road Ahead

The disclosure that 631 non-residents have acquired more than ₹130 crore worth of land in Jammu & Kashmir since 2019 marks a watershed moment. It is not just a statistic — it is a signal of a region in transition: from restricted, identity-anchored land-ownership toward an open market-oriented system.

The opportunities are real: investment, tourism growth, infrastructure, job creation. But so are the risks: displacement, speculation, cultural erosion, uneven development. The key to success will lie in governance, transparency, equity, and local inclusion.

If the government, private sector and civil society manage this shift with care, J&K can benefit from renewed economic momentum without sacrificing its unique local identity and land-rights. If they fail, this may become another chapter in the long and uneasy story of land-reform in the Himalayas—one where outsiders buy, locals lose out and trust is eroded.

As the data for 2025 and beyond unfolds, one thing is clear: land in J&K is no longer off-limits. It is being transacted, valued, owned by outsiders, and the implications will ripple across economy, society and politics for years to come.