In a Valley where an extremist leader’s grandson and a terror chief’s sons were given employment by state, father of two little daughters wasn’t as lucky.

It was spring of 2016 in the north Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. After five months in Udhampur jail, Bilal Ahmed Mohanad was a “free man”. The state High Court had just quashed his imprisonment under the Public Safety Act, despite him being sentenced to at least two years in jail.

Police had charged him with being an “overground worker” for militants, but the allegation couldn’t be proved before the court, and it ordered his immediate release.

Bilal, the son of Muhammad Yousuf from Heff village in Shopian, went back to his home in the apple town of southern Kashmir, some 80 kilometers from Srinagar, to celebrate his release with his parents, wife and two young daughters.

There was more good news. Bilal had worked as a daily-wager in the Public Health Engineering Department for 18 years for a meagre salary (around Rs 3,000 per month), but was set to be made a permanent government employee.

Official documents show that on April 20, 2016, the state government issued an order saying 218 daily-wagers would be regularized because they had worked with the department “since prior to January 1, 1994”. Bilal was 72nd on the list.

Officials who knew him said his “macho physique of a six-feet-tall hunk” had been a “bonus point” for his regularization. Engineering staff working in the field said he was often hailed as a “robust man who repairs and fits water pipes like Hercules”.

Overjoyed that his years of hard work were about to reap lifelong benefits, Bilal rushed to the office to complete formalities. The position he was being given would provide a salary of around Rs 20,000 a month, and a pension when he retired.

There was one hitch. The department required that he provide a reference from the police department. That was where Bilal’s trouble started.

The police refused to give him the “character certificate”, as he had been charged with being an “overground worker for militants”. Bilal, his family said, objected and noted that the court had exonerated him of all charges.

And despite repeated requests, they remained reluctant to issue the certificate he wanted.

His elderly father Yousuf said: “Bilal found his dreams shattered. Helpless, he spent time sitting idle at his home, unable to do anything for his family, especially his little daughters.”

Meanwhile, Heff village, in the Pir Panjal range, had become a hotbed of armed insurgency. Militants, mainly from the pro-Pakistan Hizbul Mujahideen, moved around freely, and openly brandished guns.

Amid the rise of militancy, police in the area began to summon Bilal frequently to enquire about his activities. Yousuf said: “My son would be interrogated and humiliated by the police. And this repeated humiliation was killing him by inches.”

To make things worse, the militants became suspicious of his frequent visits to the police station. Villagers say rumors spread that “Bilal is a police informer and this was why his detention was quashed.”

As per the family, he continued to bear with the uneasy situation for around three months, till July 8, when Hizbul commander Burhan Muzaffar Wani and his two colleagues were killed by security forces in Anantnag.

Kashmir erupted after Wani’s encounter, and militancy-infested Heff became the hub of pro-freedom protests. Bilal, along with hundreds of villagers, would often take to the streets. And amid the uprising, police would summon him or raid his residence, “again and again.”

As per the family, “fed up”, Bilal took the biggest decision of his life. He left his home to join the Hizbul brigade and never return.

So why couldn’t Bilal get a “character certificate” if he was bailed out by the court of law? Well, police say he was “still a suspicious character.”

“He had been an over ground worker of militants and such elements have tendency to end up as being militants. But why he was released was due to some weaknesses in the prevalent criminal justice system, which needs to be strengthened to address such issues,” says a police official in know of the case.

Police say Bilal would have joined militant ranks even if he was given the character certificate.

Deputy Inspector General of Police south Kashmir, SP Pani, who has been extensively researching on global terror networks says, “This is the most convenient thing to say that he wouldn’t have joined militant ranks unless denied the certificate.”

“Nobody becomes a terrorist overnight. He had such orientations otherwise he was married, why would he join militants?” Pani asks.

But then Bilal is not the only case where government forces are accused of “forcing the youth to pick up arms.”

In May 2017, Zubair Ahmed Turay, a youth from the same town managed to flee from a local police station where he was detained on charges of stone-pelting.

A few days after his escape, Zubair released a five-minute video-clip on social media to announce his having joined the Hizbul Mujahideen and “compelling reasons” behind the decision.

“I was slapped with PSA after PSA. And even after the last one was quashed by High Court, I was not released. Instead I was facing illegal detention since three months,” Zubair was heard saying in the video that went viral. “Every effort of my father to get me released failed.”

In another similar case, Javed Ahmed Dar was among the three militants killed in an encounter in Sopore area of north Kashmir in July. His family said he would have been alive, doing his business, had police not subjected him to “repeated detentions, torture and humiliation.”

Dar, 22, son of late Muhammad Akbar Dar of Baramulla was a conductor with a long-permit truck before joining militancy ranks. He was arrested during the uprising of 2016. His family says he was tortured and humiliated and booked in over two dozen cases at multiple police stations on charges of stone pelting. In 2017, Dar went missing only to join militancy and return home in a coffin.

Senior separatist leader like Muhammad Yasin Malik, who heads Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) believes that “police torture is pushing youth to the wall and compelling them to join armed resistance.”

Malik made these remarks on July 17 while visiting the bereaved families of three slain militants from Srinagar, killed during a gunfight that day in adjoining Budgam district.

Observers believe that “home grown” militancy has emerged as a major hindrance to sustainable peace in the trouble-torn region. As per police records, since 2014, there has been a constant rise in the number of Kashmir youth joining militancy.

70 young men joined militancy in the first seven months of 2017. At least 88 Kashmiri youths joined militancy in 2016. And, as many as 66 youths joined militancy in Kashmir in 2015 and 53 in 2014, according to data compiled by security agencies.

Neutralizing militants is an unending process. This year alone, security forces have eliminated over 100 militants including eight top commanders. But despite frequent funerals, militancy continues to attract Kashmiri youth.

Security analysts believe that many of those who picked up arms were actually fed up with the system. A police officer who personally knew Bilal believes he could have been a “classical case of de-indoctrination” had he been given the character certificate.

“There are many like Bilal whose cases if handled with extra-delicacy would have saved them from picking up arms. There are a few gone cases, whose minds are poisoned to a level that they become desperate to die as militants, but others like Bilal who are fed up of life, could be brought back to life through strategic efforts,” said a top police official, who has himself killed militants during encounters, asking not to be identified.

But then, Bilal was denied police clearance in the trouble-torn region, where many of those closely related to top militants or pro-Pakistan leaders get duly absorbed in government jobs. All five sons of Hizbul Mujahideen supremo Syed Salahud Din happen to be permanent employees with the same government against whom their father has openly waged a war.

Interestingly, while the uprising against Burhan’s killing brought a turning point in Bilal Ahmed Mohand’s life, an alleged deal brokered between senior separatist leader Syed Ali Geelani and the government for restoration of normalcy that year, facilitating the latter’s family member getting a government job.

In the winter of 2016, Geelani’s grandson, Anees Ul Islam secretly joined government services through a “backdoor,” when police issued a character certificate in his favour. Back in 2009, though, police had denied clearance to Anees for grant of passport due to his alleged connections with militants.

But then, for Bilal, who seemingly enjoyed no influence, the government used a different yardstick.

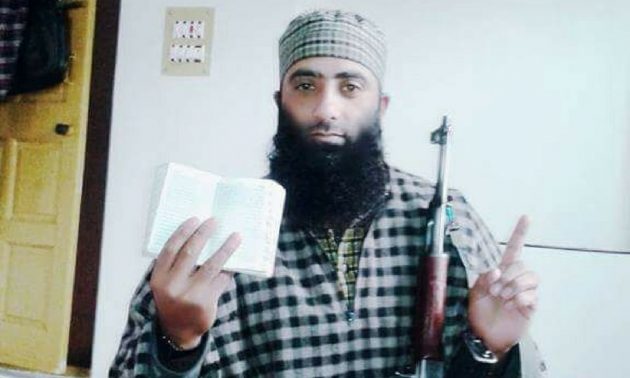

The man who struggled for almost two decades to get a permanent government job, has picked up arms against the same government. And he has become one of the most wanted militants in the state, with a reward of Rs 5 lakhs on his head.