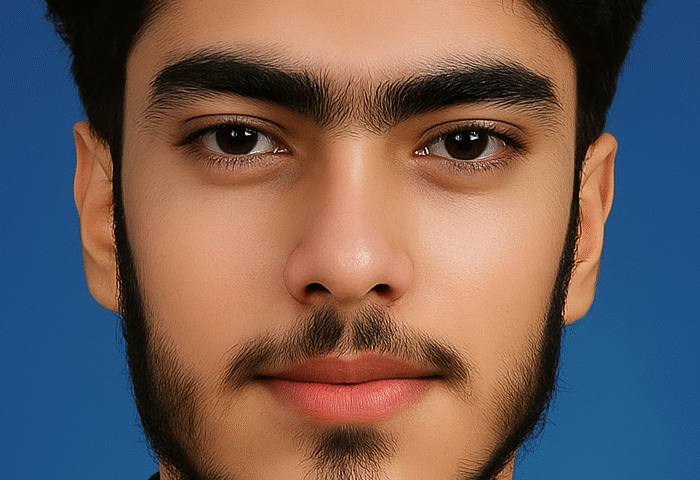

His friends saw him lying in a pool of blood on the street and they lost hope. A tear gas shell had struck his head during protests. Showkat Ahmed, 18, regained senses two days later after an emergency operation in the neurosurgery ward of Srinagar’s Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) hospital, about 80km away from Handwara in northern Kashmir, where he had suffered the near-fatal injury.

His friends saw him lying in a pool of blood on the street and they lost hope. A tear gas shell had struck his head during protests. Showkat Ahmed, 18, regained senses two days later after an emergency operation in the neurosurgery ward of Srinagar’s Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) hospital, about 80km away from Handwara in northern Kashmir, where he had suffered the near-fatal injury.

“Why did they hit me?” Ahmed asks, barely able to open his eyes. “I was not even part of the protests. I had come out of my house looking for my cousin when something hit my head and I fell down,” he repeats before losing consciousness.

An emergency surgery in the nick of time saved total brain damage, doctors informed his family.

Zahoor Ahmed, one of his cousins, expectedly enraged, said that the Army personnel didn’t let them come near him as he lay bleeding, unconscious, and wasted over 25 minutes before they could take him to the hospital. “He was hit in the head with an intention to kill. We are sick of this ‘state terrorism’. We don’t trust anyone. We can’t trust the media or the government.”

Ahmed survived. It’s a miracle. But five others including a 19-year-old cricketing star and a homemaker, who was shot in the head while she was tending to her kitchen garden, perished in the recent unrest following allegations of molestation of a 16-year-old girl by an Army personal in Handwara on April 12.

Zahoor, 21, echoes the angst among young Kashmiris, whose home forever remains in the grip of unrest; who have seen unarmed men, women and children losing their lives in armed forces’ firings during street protests; and who feel pushed to the edge. About 120 people (official figure) were killed in the youth-driven agitation of 2010 who were protesting the mutilation of three young men who were passed off as “Pakistani terrorists”.

During the recent protests at the University of Kashmir, an enraged student says he feels helpless in the face of atrocities. “Yes, Kashmir enjoys a special status. Where else does it take deaths of five unarmed civilians to get rid of three Army bunkers (in Handwara)?” he asks.

“Where else would stone-throwers be dealt with bullets? Where else would a woman, humming verses of (mystic poetess) Lal Ded, die of a bullet injury while tending to her kitchen garden? Where else would a journalist, who goes to report, find the bullet-ridden body of his brother (the budding cricketer) in the hospital?”

Nirbhaya protests in Delhi were controlled with water cannons. Students’ agitations elsewhere in India are handled efficiently. Then why does our blood become cheap?”

Had the alleged molestation happened elsewhere, the media would have asked serious questions. It would have questioned why a minor girl was detained, which is clearly against the law, or why her identity was revealed and her video circulated online, he questions.

“Even if the girl was not molested or who molested her wasn’t clear, what legitimises the killings of four people?” asks Khurram Parvez, convener of Coalition of Civil Society, a human rights group. “There might be some confusion about what actually happened to the girl, but the killings are real,” he says.

The extrajudicial killings were not the first instance encouraged by the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) that gives the Army sweeping powers and immunity from prosecution. The law violates even the most fundamental right to life and was introduced in the 1990s to tackle Kashmiri insurgency. It has continued to remain in force despite negligible militant violence since 2004,as per records, and facilitated extrajudicial killings, torture and arbitrary arrests with impunity.

“We do not have faith in the so-called probes. The Army enjoys immunity under the AFSPA. We cannot do a Jawaharlal Nehru University-style of agitation and would not have a Kanhaiya Kumar because if I dare to raise my noise, I will be booked under Public Safety Act (administrative detention law),” says a student from Downtown, Srinagar.

While revocation of draconian laws remains a distant dream, the use of “non-lethal” force and the Army’s tendency to shoot at unarmed protesters continues.

Doctors maintain that the non-lethal weapons — marbles fired from slingshots, pellet guns and pepper grenades packed with chemicals – have caused grievous injuries to people.

Various researches by medical professionals and international agencies like Amnesty International in 2013 suggest that the children and the elderly were particularly vulnerable to chemicals in pepper grenades that have blinded many.

Experts even argue over the legal status of the use pepper gas grenades as India is a signatory to an international chemical weapons protocol.

In fact, the 2010 protests had escalated after a non-lethal tear gas shell blew the brains of a 17-year-old school boy, Tufail Mattoo, who was on his way to coaching classes.

Over the years, numerous protests have happened and forgotten. Little has changed. Thus the pent-up anger.

Among those injured at SMHS hospital is 15-year-old Danish Ashraf from Handwara, who could lose his eyesight. Ashraf, too, was on his way to tuition classes when a tear gas splinter hit him in the eye. “The Army went on a rampage. They broke the glasses of the windows. The kid is innocent. But he is a victim now,” says Ashraf’s cousin. “One feels angry and helpless. This is perhaps how a stone-pelter is born,” he adds.

A Srinagar-resident cites a recent US State Department report that blames Delhi for using AFSPA “to avoid holding its security forces responsible for the deaths of civilians”. “We see no light at the end of the tunnel,” he says.

“When five people were killed in Handwara, our chief minister was meeting BJP president Amit Shah. When she was sitting in the Opposition, she was the worst critic of the draconian laws. The writing on the wall is clear to us. Justice is a distant dream,” he says.

The media’s alleged role in justifying the killings amid a pervasive culture of impunity and lack of closure is contributing to their exasperation. Brutal suppression of any form of protest, like the closure of Srinagar’s main mosque for weeks, has worsened the situation.

“Don’t write about us, if you can’t write the truth,” Zahoor signs off.

Don’t write about us, if you can’t write the truth: Kashmiri youth