It was a usual militant funeral for Shariq Ahmad Bhat, killed in a night-long gunfight with security forces this week. Hundreds of mourning men and women had gathered at Braw-Bandina village of Pulwama, slogans were raised and mobile phone cameras were put on record mode.

Bhat, a young and tall man, was killed at Naina village of Pulwama, one of the four districts that make up south Kashmir.

Bhat, a young and tall man, was killed at Naina village of Pulwama, one of the four districts that make up south Kashmir.

At Bhat’s funeral, an unusual event unfolded — one that is helping create an aura around the militant lives and their deaths.

Three men wearing phirans (long winter cloak), carrying Kalashnikov rifles and faces covered made their way towards Bhat’s body. The crowd of mourners grew euphoric on seeing them — Riyaz Ahmad Naikoo, Lateef Ahmad Dar and Ishfaq Ahmad Dar.

As one of them hugged Bhat’s body and touched the slain militant’s face, Naikoo fired several shots in the air from his Kalashnikov. The firing was a revival of an earlier tradition of militants to pay tributes to their fallen comrades.

The entire scene was captured in a video on a mobile phone camera and the visuals became viral, circulated over instant messengers and social networking sites.

Though such incidents are rare, there has been a consistent outreach by militants in the region to connect with locals as insurgency continues in its third decade.

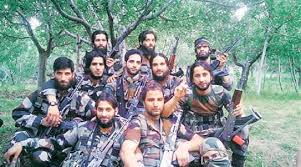

The militants operating in south Kashmir, which has emerged as the new flashpoint of insurgency in recent years, have maintained a constant contact with people by releasing their photographs and videos, giving a human face to the insurgency that has remained masked in anonymity.

The number of militants in the Kashmir region has sharply declined over the last decade. However, a new wave of recruiting young men, willing to fight with limited resources, has kept the insurgency growing. Their latest figure is believed to be between 150 and 200.

The void left by dead militants, like Bhat, is quickly filled by a steady flow of new recruits, most of them drawn from villages and towns of south Kashmir in recent years.

In the aftermath of widespread street agitation through the summer of 2010, militants have successfully restarted recruitment, which had dropped to an unprecedented low.

In the past two years, between 100 and 150 local youths, some of them highly qualified, have joined a fading insurgency and provided it enough manpower to maintain a significant presence.

A total of 73 militants — 67 of them locals — are operating in south Kashmir, according to a latest police assessment. The Hizbul Mujahideen, one of the oldest militant groups operating in the region, has the highest footprint with 42 men. There are no foreign militants in the group.

A total of six foreign militants operate in south Kashmir. They work with the Lashkar-e-Toiba or the Jaish-e-Mohammad.

“The militants, however, are often found to be working in tandem, crossing over the organisational line,” said a police officer posted in Pulwama district.

Even as security officers consider local militants a more potent threat as they provide more sense and depth to the insurgency with their knowledge and understanding of regional sensibilities, cultures and topography, they are also easy to identify targets.

“For our human intelligence network, it gets easier to recognise a specific (local) target and track his movements,” said a police officer in south Kashmir’s Anantnag district.

The region’s powerful counter-insurgency grid, which has a wide human intelligence network and a robust technical intelligence mechanism, has maintained a perpetual pressure on the militants in the region limiting their age to 12-18 months. Some militants die without even firing a shot before their last encounters with security forces.

The new militants — even as they have succeeded to maintain a presence in most districts of the Valley — have failed to carry out major attacks against security forces, as was done in previous decades.

With some exceptions, like the ambush of an Army vehicle in August 2013 in which eight soldiers were killed on a highway on the outskirts of Srinagar, the militant actions have been limited to occasional hit-and-run attacks, chance encounters and lobbing of grenades, which mostly missed the targets.

Most of the militants operating in the region have picked up arms in the last two years and have been trained locally as crossing the Line of Control for arms training involves higher risks.

The lack of battle-hardened men in militant ranks is partly a reason for the increasingly ineffective and less lethal insurgency in the region.

“It is a combination of many factors,” said SJM Gillani, Inspector General of Police for Kashmir zone.

“We have had very good counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations, so they are on a back foot and with the results their numbers are dwindling. It is also the preventive measures which we take,” he said.

Since January 2015, 34 militants have been killed in south Kashmir’s four districts, many of them inside their hideouts during counter-insurgency operations by security forces.

Despite their dwindling number, the militants are stealing the show by continuing the fight which has no sign of an end. Their funerals, like the one which Bhat got on Thursday this week, are attracting crowds of mourners and their graves are becoming sites of reverence. In Kashmir’s uneven war, militants are winning the battle for hearts.

A steady trickle of fresh recruits keeps insurgency alive in Valley