When Indians ask this question, they answer it themselves and on their own terms.

Honestly speaking, I had never heard of Burhan Wani until reading about the formidable crowds that formed his funeral procession. I am learning, after his death, that he was a Kashmiri who, like many others, experienced first-hand the peremptory brutishness of the armed forces representing the Indian occupation of Kashmir. Deployed through many different gestures – from unnecessary beatings, to needlessly humiliating demands for identity proofs, to lewdness towards women — the coarse affronts (leave alone killings, rapes, disappearances, torture) by those exercising Indian dominance are an everyday, near-ordinary, occurrence intended to choke all sense of dignity and honour out of the Kashmiris. Wani had clearly crossed the threshold of forbearance very young; he was 16, I hear, when witnessing the gratuitous thrashing of his elder brother turned him to armed militancy. But to tell the story in this way is to infantilize Wani and others like him; armed resistance was not an expression of pique. Wani fought to end India’s stranglehold over his homeland; he, like many of his compatriots, understood well that the physical assaults and insults meted out to them were only the symptoms of a deeper colonisation.

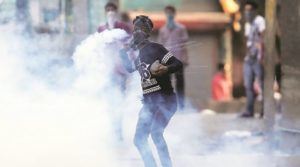

An observation made many times before, especially in the aftermath of the bloody summer of 2010, bears repeating: The generation that has come of age today in Kashmir comprises individuals like Wani who have only seen the forceful subjugation of the Valley. And they are, like him, aware that any open resistance means certain death or, perhaps worse still, being simply “disappeared”. However, it must be emphasised that Wani’s method of armed war is not that of most Kashmiris, even if they “support what he stood for”.

Constant reference to Burhan Wani as the “poster boy” of the Hizbul Mujahideen reduces him to a social media butterfly. It also effectively takes the sting out of the threat he represented; no ski-mask or mostly-veiled face for him. Undisguised, he offered up his identity on the most widely spread medium of this age and challenged subordination by calling for the killing of Indian armed forces — no occupation can stomach such audacity. As an open letter, circulating recently, addressed posthumously to Wani by an Indian army “veteran” put it, Wani was a “dead man” as soon as he began his “social media blitzkrieg”.

By contrast, working under the cover of darkness, during the night of July 15-16, J&K government officials ordered shut the publication of Kashmiri newspapers. According to the senior leader of the PDP Naeem Akhtar’s initial statement, this was a “reluctant” decision necessary to soothe the emotionally febrile valley. Since then the political advisor of the chief minister has denied that Mehbooba Mufti had any knowledge of this measure. Nor, incidentally, we are now told, was she informed about the operation that killed Wani and his two companions. An information blackout seems to have engulfed the executive head of the state herself.

At any rate, whether or not the CM ordered the ban on newspapers, the absurdity of the measure lies in its utter futility. It does not require a gag order for most Indians to be ignorant about Kashmir. Turning a deaf ear and a blind eye have become the naturalised stances of not only the Indian state and the corporate-owned media but also of large sections of India’s citizenry. Fed on a regular diet of jingoism, boosted with self-myths of being a superpower (at least regionally), a tolerant society, nearly-developed, and equipped with the wisdom of all the ages, why should they pay attention to Kashmiris? There is a refusal even to accept Kashmiri alienation — the very use of the “a” word provokes conniptions in a certain spokesman of the ruling party of India. He also bristles to hear Kashmiris repudiate India and its armed forces as theirs. On July18, debating in the Rajya Sabha, India’s home minister was brazenly (self?) deluding: “Kashmiris are our own people. We will bring them on the right path.” The right path is presumably the Hindu, as opposed to the Muslim.

Recently, a number of journalists have rediscovered fire again and once more. They warn us against the radicalisation of Kashmiris — obviously the Muslims, because radicalised Hindus are nationalists — that must be countered. How many times can the Kashmiri Muslims be “suddenly” radicalised? The political scientist, Sumit Ganguly, had found a new Muslim radicalisation among Kashmiris in the 1980s. The Dogra state and various state-dependent Kashmiri Pandits had found that about half- a-century before. When their Dogra rulers (the current political dispensation at the centre is not very different) had no compunctions about deriving their legitimacy from Hindu religious and cultural traditions, how could Kashmiri Muslims be prevented from similarly drawing idioms of resistance from their faith? Not every reference to religion tantamounts to bigotry. But how can you expect such comprehension from a citizenry that cannot differentiate between a militant and a terrorist?

Is it ungenerous not to acknowledge a change in Indian opinion when individuals like Shobhaa De begin to interest themselves in “What Kashmir really wants” (The Times of India, July 17)? De calls for a referendum and that is nice. But have the Kashmiris not been repeatedly screaming out loud in their unarmed processions — facing bullets and pellets, enduring loss of life, limbs, sight and liberty — the results of what are referenda by other means? Besides her proposal — however laudable — when phrased as a dare to this current government, given its hawkish nature, sounds facetious and is easily punctured: Rajnath Singh did so when he declared the idea of a plebiscite “outdated”.

In any case, the question about what Kashmiris really want is hardly a new one. The trouble is when Indians ask this question they generally answer it themselves and on their own terms. Remember the trio of interlocutors appointed in October 2010 to tour the valley interrogating every Kashmiri willing to speak to them? They went armed with the same question.

Oddly, as they mention on the first page of their report, they detected a “deep sense of victimhood prevalent in the Kashmir Valley”. Victimhood? Not rebellion? Furthermore, a point on which they found “a broad consensus exist[ed]” was that “Jammu and Kashmir should continue to function as a single entity within the Indian Union”. I must have my valleys confused.

According to a certain television journalist, what Kashmiris really want is the “healing touch”. How, she asked while discussing the damage caused by “pellet guns”, can Indian armed forces be less lethal in Kashmir? The answer should have been: By ending the occupation. Predictably, it was not. What Indians need is the ability not just to hear but to listen. It does no good to ignore or mangle the words — containing both the question and the answer — Kashmiris have spoken time and again: “Hum Kya Chahtey? Azaadi.”